tânisi nitôtêmitik, welcome to Treaty Talk With âpihtawikosisân!

In previous episodes, we’ve explored the way in which modern treaty making resembles the approach taken during the creation of the historical numbered Treaties. We’ve also looked at how ‘without prejudice’ agreements stall and perhaps undermine the maintenance and exercise of Aboriginal rights, as an alternative to real treaty-making.

Today, we’re going to go back, back in a time a little.

Early treaty making in Canada

For some time in our early relationship, colonial powers dealt with indigenous peoples on a fairly equal basis. This was of course during a time when European numbers were low in comparison to the indigenous population, and at a time when Europeans desperately needed help to survive these climes as well as surviving the military aggression of their fellow Europeans. Treaty making during this period focused on these specific needs and were not about land so much as they were about securing military and economic aid from the eastern First Nations.

Growing up in the west, I knew very little of these kinds of treaties. My relations live mostly in Treaty 6 and Treaty 8 territory, so my understanding of treaties as a thing was very coloured by that context. The idea of treaties not being about taking land and shoving native peoples on to successfully smaller and crappier pieces of land was just something I hadn’t considered as being possible.

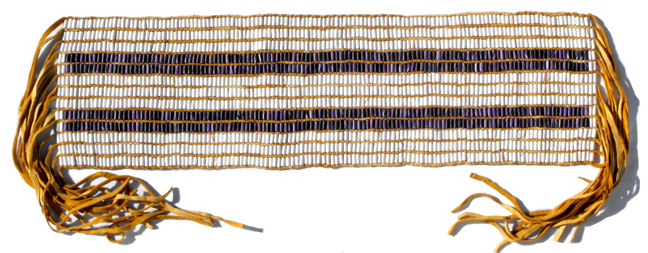

To be honest, I don’t think I really ‘got it’ until I came and lived in the east, and became surrounded by this earlier view of treaty-making. I took my daughters to Darren Bonaparte’s wonderful presentation of the “Wampum Chronicles” last year, and all of our moccasins were blown off by a very coherent explanation of the timeline and purpose of those early treaties. The various bits and pieces I had learned over the years from members of those eastern nations finally came together in my mind, and I was left thinking, “we need to get back to this kind of relationship”.

When the wholesale acquisition of land does not even truly enter the equation via treaty, it is much more difficult to claim that the original intentions were indeed ‘you give us everything, and we regift you a tiny piece back’.

The Gradual Civilisation Act

The period of ‘Contact and Co-operation’ (as it has been styled in the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996 report) was followed by a period of heavy-handed colonialism. European settlement, already begun in earnest after the 1780s as Loyalists flooded into Mi’gmaq and Maliseet lands, increased significantly after the war of 1812. The Robinson Treaties began ‘opening up lands’ for settlement and the population tide shifted very much in the European’s favour.

The period of ‘Contact and Co-operation’ (as it has been styled in the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples 1996 report) was followed by a period of heavy-handed colonialism. European settlement, already begun in earnest after the 1780s as Loyalists flooded into Mi’gmaq and Maliseet lands, increased significantly after the war of 1812. The Robinson Treaties began ‘opening up lands’ for settlement and the population tide shifted very much in the European’s favour.

An Act to Encourage the Gradual Civilization of Indian Tribes in this Province, and to Amend the Laws Relating to Indians, was passed in 1857. (By this time, my community of Lac Ste. Anne had an established Mission in an area peppered with the children and grandchildren of Louis Callihoo Kwarakwante.)

This Gradual Civilization Act opens with the following:

WHEREAS it is desireable to encourage the progress of Civilization among the Indian Tribes in this Province, and the gradual removal of all legal distinctions between them and Her Majesty’s other Canadian subjects, and to facilitate the acquisition of property and of the rights accompanying it, by such Individual Members of the said Tribes as shall be found to desire such encouragement and to have deserved it….

They sure didn’t mince their words back then! “We want there to be no more such thing as a category labelled ‘Indian’!” This Act introduced the idea of enfranchisement, where Indians stopped being Indians and instead became British subjects. This was seen as a positive thing because of course, ceasing to be Indian meant you were civilised. Yeeeeehaw!

This desire to assimilate aboriginal peoples into ‘mainstream Canadian society’ for our benefit, is one that remains deeply entrenched in the Canadian socio-political consciousness. It was also a major theme throughout various pieces of legislation that proceeded the Indian Act.

The Indian Act is born

The first iteration of the Indian Act was brought into the world in 1876. This marked a definite shift from an earlier approach which viewed indigenous peoples as autonomous quasi-nations which were to be protected from molestation by unsavoury characters. The belief that indigenous cultures and societies were inferior passed into official policy:

Our Indian legislation generally rests on the principle, that the aborigines are to be kept in a condition of tutelage and treated as wards or children of the State. …the true interests of the aborigines and of the State alike require that every effort should be made to aid the Red man in lifting himself out of his condition of tutelage and dependence, and that is clearly our wisdom and our duty, through education and every other means, to prepare him for a higher civilization by encouraging him to assume the privileges and responsibilities of full citizenship.

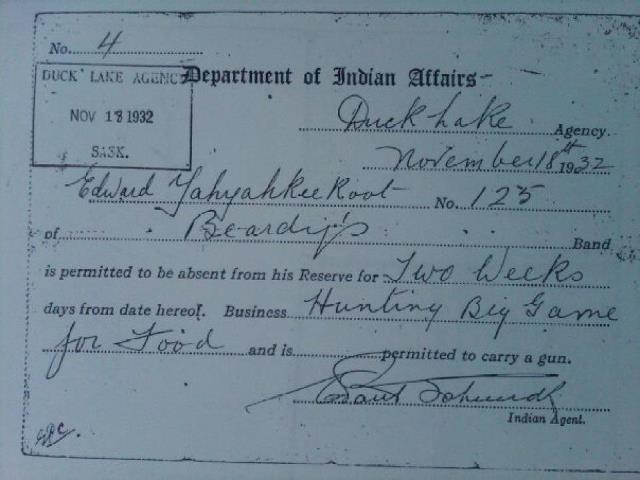

This is a 1932 pass, giving permission to its holder to leave the reserve. The pass system was official policy in the Prairies but never had a legislative basis.

‘Civilising’ the ‘aborigines’ under the Indian Act (at the same time that the numbered Treaties were being made) meant micromanaging every aspect life for Indians. Here are some highlights from among the various amendments made to the Indian Act over the years:

- 1885: Prohibition of several traditional Aboriginal ceremonies, such as potlaches (sundances were outlawed in 1895).

- 1905: Power to remove Aboriginal peoples from reserves near towns with more than 8,000 people.

- 1911: Power to expropriate portions of reserves for roads, railways and other public works, as well as to move an entire reserve away from a municipality if it was deemed expedient.

- 1914: Requirement that western Aboriginal peoples seek official permission before appearing in Aboriginal “costume” in any public dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant.

- 1918: Power to lease out uncultivated reserve lands to non-natives if the new leaseholder would use it for farming or pasture.

- 1927: Prohibition of anyone (Aboriginal or otherwise) from soliciting funds for Aboriginal legal claims without special licence from the Superintendent General. This amendment granted the government control over the ability of Aboriginals to pursue land claims.

This last one is a Big Deal. Treaty 11 was signed in 1921, marking the end of the signing of numbered Treaties. A great many claims of Treaty violations were starting to come forth, and Canada legislated away our ability to seek any recourse. The Pass System, enacted in the Praries but not written into law, helped prevent indigenous peoples from ‘collaborating’ to pursue grievances as well. This provision was not repealed until 1951.

The glacial pace of negotiations

Most Canadians cannot comprehend why on earth these issues have not yet been resolved. How can there still be land claims? What the hell is going on?

Well, there was no federal comprehensive land claim policy until 1973. Between 1927-1951 it was illegal to raise funds to pursue claims, and then it wasn’t until 1973 that any sort of framework was put in place to hear them anyway (outside the courts).

That is a significant period of time within which, we were unable to do anything to pursue land claims or seek recourse for treaty violations. It took some nations up to 32 years to settle land claims (page 13 has a chart), even though they filed their claims mere days or months after the federal system was set up. Many others claims launched around the same time have not yet been resolved, and still other claims were stalled and not launched until the 90s or early oughts.

Let’s keep this in perspective, shall we? The numbered Treaties were signed within 50 years, between 1871-1921. NINETY-ONE YEARS LATER and there are a vast number of unresolved claims sitting in Canada’s ‘inbox’.

Have we advanced so little in nearly a century, that we still haven’t resolved these issues? Canada, you can do better.

Are we human, or not?

This article is intended to very briefly outline a context that you may not be familiar with. Canada did not just wake up one day and decide that treating us like inferiors was wrong. The whole notion that we might indeed be human beings, equal in worth to non-natives, is a very recent shift, and not one that has fully gained traction yet.

I want you to keep this in mind when I finally get down to writing about the way aboriginal organisations are being slashed and burned wholesale. I want you to remember the way the relationship between indigenous peoples and Europeans began, and how that changed.

I want you to think about the stated goals of assimilation (civilisation), and of the intense restriction of indigenous lives, and whether this is something you support? Was it not okay back then? Is it okay now? What do you think has changed?

The Indian Act is just one piece of legislation. Furthermore, it applies only to Status Indians. Nonetheless, it represents a series of beliefs and approaches that have been applied to all indigenous peoples in Canada throughout this nation’s history.

I firmly believe that if Canadians were to view this situation through a ‘foreign’ lens, as though it were happening somewhere else, it would be quite easy to condemn. Familiarity does tend to breed contempt, however, and the myopic view this nation has of its relationship with indigenous peoples seems to shroud the dialogue in a cloud of justificatory claims such as ‘well our situation is different’.

The current climate is hurtling us dangerously backwards in time. If that meant we were going to return to a pre-Confederation, egalitarian approach to treaty making, then I’d be all for it. But let’s not be silly, because that is not what is happening. If anything, the current budget slashing and time-frame restrictions are emulating 1927 Indian Act restrictions, making it more and more difficult for us to actually resolve these problems. Nor will this change, unless Canadians want it to.

We have to fix this relationship eventually. Are we going to put it off for another century?

10 Comments

Perry Bulwer · May 18, 2012 at 4:23 pm

In the current issue of The Advocate, published by the Vancouver Bar Association, there is an article entitled “Three Points About Aboriginal Title”, by Douglas Lambert. It is based on a speech he gave to the Assembly of the Haida Nation. The article is not online yet, but it is in Volume 70 Part 3 May 2012 in case you want to look for it later. I’ll just provide his summary of those 3 points.

1. The Continuation of Past Discrimination: This point, in summary, is that our sovereign governments should stop denying First Nations the legal titles and rights that have been recognized and affirmed in the Constitution, and should instead concentrate on working toward reconciliation of those titles and rights with Crown sovereignty through negotiated accommodations and by refining the legal principles of justified infringement.

2. The Date of Sovereignty and the Douglas Treaties: This point is that the language and matrix of the Douglas Treaties, made between 1850 and 1854, are supremely relevant contemporaneous guides to what was then considered to be exclusive occupation for the purposes of demonstrating aboriginal title in 1846, the date of sovereignty. [for B.C.]

3. The Significance of Marshall and Bernard: My third point is that Chief Justice McLachlin in Marshall and Bernard did not say that she was changing the law, and she wasn’t. Aboriginal title and rights were sui generis before that decision and they still are. What Chief Justice McLachlin was doing was giving some additional explanation of the vocabulary required in order to make aboriginal title and rights, based on First Nations perspectives, comprehensible within the common law and civil law systems.

Samson · May 22, 2012 at 8:25 pm

You go girl! This is fascinating reading.

Lynda Gray · May 28, 2012 at 6:42 am

Being Métis I am interested in Aboriginal Affairs — thanks for posting this.

Lynda

bob the fish · November 7, 2014 at 2:16 pm

this is dumb. very boring :/

âpihtawikosisân · November 7, 2014 at 7:33 pm

Lol, thanks so much for taking the time to comment!

The Answer Is 42 · November 16, 2012 at 3:07 am

[…] This should remind you of South African Apartheid for the simple reason they developed their system from the Canadian reserve system. […]

#IdleNoMore: Indigenous Women Spark a Movement | Gender Focus – A Canadian Feminist Blog · December 13, 2012 at 8:33 am

[…] the relationship between indigenous peoples and Europeans first began here, it was based on Treaties of Peace and Friendship. As indigenous peoples understand this relationship, it is one that should work to the mutual […]

Eradicating Ecocide in Canada - Court refutes Harper government: Attawapiskat was not financially mismanaged · January 8, 2013 at 12:16 pm

[…] First Nations based on things like misunderstanding the scope of First Nations taxation, and Treaties, as well as a lack of understanding that colonialism is not a merely historical […]

Round dancing at the mall » StraightGoods.ca · January 12, 2013 at 9:01 pm

[…] between indigenous peoples and Europeans first began here, we had a relationship based on Treaties of Peace and Friendship. As indigenous peoples understand this relationship, it is one that should […]

November 2-8- Treaties Recognition Week in Education – Ed Aid Ontario · November 4, 2020 at 11:26 am

[…] Treaty Talk With âpihtawikosisân […]