If you’ve ever heard the term “60s scoop” and thought it had something to do with ice-cream in the old days, I’m here to enlighten you.

I prefer the term Stolen Generations, because the scooping I’m about to discuss did not end in the 60s. In fact, many argue that it didn’t end with a single generation either, and perhaps hasn’t actually ended at all… hence the title. Similar policies were put into place in Australia with equally unhappy results.

You could delve into this sordid history and lose many hours uncovering details, but I’ll provide you with a brief outline and enough links to allow you to do that digging if you wish. I recognise that some people will find my style overly hyperbolic. Personally, I don’t feel I’m able to give these topics justice in the short space I’m allowing myself.

Adoption as Cultural Annihilation

It is important to remember that many of the services Canadians take for granted, such as education, health care, and social welfare programs are in the main, designed and administered by the provinces and territories.

Some survivors of the 60s scoop are pursuing a class action lawsuit against the province of Ontario and Canada.

However, the federal government has been asserting its authority over “Indians and Lands of the Indians” since 1763. While is still remains unclear whether this includes all Inuit and Métis, it remains true that First Nations must turn to the federal government, not the provinces, for many services.

Canada did not spring from the skull of Zeus fully formed. The development of social programs and services has been incremental. Before the mid 1960s, there was no organised federal child welfare system. The provinces each had their own system, but nothing was in place for First Nations people.

In the mid 60s, agreements started to be formed between the federal and provincial governments to provide some child welfare coverage in First Nations communities. To be brief, the approach was “take first, ask questions later (if ever)”.

The similarity to tactics used during the height of the Residential School system is eerie. Aboriginal children were taken en masse from their families and adopted out into non-native families:

Child welfare workers removed Aboriginal children from their families and communities because they felt the best homes for the children were not Aboriginal homes. The ideal home would instill the values and lifestyles with which the child welfare workers themselves were familiar: white, middle-class homes in white, middle-class neighbourhoods. Aboriginal communities and Aboriginal parents and families were deemed to be “unfit.”

Research has shown that in British Columbia alone, the percentage of native children in the care of the Child Welfare system went from almost none, to one-third in only 10 years as a result of this expansion. This was a pattern that repeated itself all across Canada.

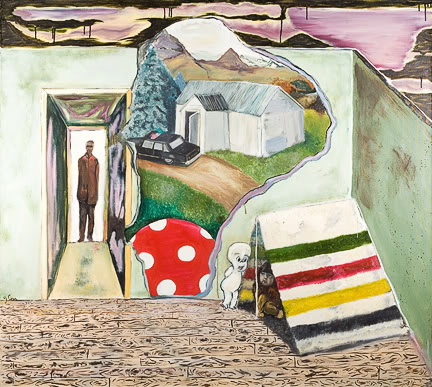

Survivors have been trying for years to be heard. To learn more about the legal struggle, click on the picture above.

There is evidence that at least 11,132 Status Indian children were removed from their homes between 1960 and 1990. However, it is clear the numbers are in fact much higher than this, as birth records were often closed and Status not marked down on foster records. Some estimate the number, which included non-Status and Métis children, is more like 20,000.

Being from a native family was often enough to have a child declared in need of intervention. This process resulted in thousands of indigenous peoples being raised without their culture, their language, and without learning anything about their communities. Reclaiming that heritage has been a painful and difficult journey not only for the adoptees themselves, but often also for their families.

The 60s scoop picked up where Residential Schools left off, removing children from their homes, and producing cultural amputees.

Child Welfare reforms not working

In the late 70s, it was recognised that the approach up to that point was inadequate. There were efforts made to turn more power over to First Nations themselves and to keep children in their communities rather than being adopted out across Canada, into the US and even overseas.

In 1982, Manitoba Judge Edwin C. Kimelman was appointed to head an inquiry into the Child Welfare system and how it was impacting native peoples. He had this to say:

It would be reassuring if blame could be laid to any single part of the system. The appalling reality is that everyone involved believed they were doing their best and stood firm in their belief that the system was working well. Some administrators took the ostrich approach to child welfare problems—they just did not exist. The miracle is that there were not more children lost in this system run by so many well-intentioned people. The road to hell was paved with good intentions, and the child welfare system was the paving contractor.

Nor was this his strongest condemnation of the process, and he made it clear that the system was a form of cultural genocide.

Unfortunately, by 2002 over 22,500 native children were in foster care across Canada, more than the total taken during the 60s scoop and certainly more than had been taken to Residential Schools. Aboriginal children are 6 to 8 times more likely to be placed in foster care than non-native children. To ignore the repeated attempts to annihilate aboriginal cultures and instead place the blame solely on ‘dysfunctional native families’ is to take an utterly ahistorical and abusive view.

…[this] over representation…is not rooted in their indigenous race, culture and ethnicity. Rather, any family with children who has experienced the same colonial history and the resultant poverty, social and community disorganization…may find themselves in a similar situation.

Systemic discrimination and underfunding

On April 18th, an historic ruling came down from the Federal Court regarding the underfunding of Child Welfare services on reserve. This case is a judicial review of a decision made by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal,which dismissed the claims on a technicality.

The Federal Court has sent the case back to the CHRT for a full hearing.

Repeated studies have shown funding for child welfare on reserves is far below that available to children off-reserve and results in far lower levels of service. In particular, the lack of funds available for programs that can help families before they are broken up results in far higher rates of children being taken into foster care on reserves than off reserves.

The rate of foster care for reserve children is about eight times that of non-aboriginal children, concluded former Auditor General Sheila Fraser in 2008.

When the complaint was filed, the federal government generally spent about 78 cents on child welfare on reserves for every dollar spent by the provinces for children on reserves.

No situation involving children in need of protective services is a happy one. The stories regardless of the background of the child will chill your blood, and rightfully so. But when only 21% of children in a province like Manitoba are native, yet account for 84% of children in permanent care, something is deeply, and terribly wrong. Something that cannot be chalked up to just bad parenting.

What makes the situation even more troubling, is the fact that deplorably common conditions found on reserve work against families, not only resulting in children being removed, but also making family reunification out of reach for many.

The main reason aboriginal children enter the child protection system is due to “neglect” (with significantly lower rates of physical abuse than is experienced by non-native children in child welfare cases).

Neglect in cases involving aboriginal children is “driven primarily by 3 structural risk factors: poverty, inadequate housing and substance misuse.”

Inadequate housing is a serious, systemic problem in many First Nations communities. Overcrowding, lack of indoor plumbing or potable water, mould-infested homes and crumbling infrastructure all play a part in what constitutes “inadequate housing”. It is also a factor that is rarely something the families in question can directly control. Attawapiskat recently provided stark evidence of this.

Aboriginal children, and their families, are being punished for being faced with unacceptable living conditions that no one living in Canada should have to contend with.

The legacy of over a 100 years of concerted cultural abuse, particularly directed at taking children away from their families, has taken its toll on our communities. There is no denying it. In my opinion, the question now needs to be…will Canada acknowledge this and do what it takes to redress these wrongs?

Money alone is not going to solve this problem. Real change needs to occur, and it’s going to start with the story being fully understood.

Many thanks for listening.

35 Comments

Ray Battams · April 21, 2012 at 6:42 pm

Your work is always so valuable and insightful. I will share it.

Sharon Jackson · April 21, 2012 at 6:57 pm

If you have not seen the movie, “The Rabbit Proof Fence” about aboriginal children in Australia, it is very worthwhile and an amazing tribute to the human spirit.

john lavers · April 21, 2012 at 10:00 pm

i agree. the tragedy of the conservatives comming to power was that the last liberal government had negotiated the kelowna accord and the last budget–which defeat brought down the government–had ear marked six billion dollars to fund a variety of new initiatives to address the inequality natives have faced. this accord may not have been perfect but it was the right direction and now that’s all gone. i still can’t believe the ndp voted down the budget for the kelowna accord

canada has been inflicting genocide on natives since the beginning and we can’t be a just and honest nation untill we address these issues in a real and effective way.

Katherine Hensel · April 21, 2012 at 10:04 pm

As an advocate for First Nations in child welfare proceedings, I am often appalled by the contemporary approaches of many workers, agencies and (unfortunately) even some courts, which differ not at all from the “well-intentioned” approaches that led and now lead to the widespread apprehension of children and their separation from loved ones, community and territory. But it is harder to characterize such initiatives as “well-intentioned”, considering what we now know about adoption breakdown, cultural alienation, and the bleak, often tragic outcomes for adoptees.

Khelsilam · April 22, 2012 at 3:19 am

Oh my ancestors! You’re in depth explanation of important aspects of history — but in an approachable non-academic way — is simply amazing.

Thank you for providing this valuable resource. Please don’t stop.

Trace A DeMeyer · April 22, 2012 at 12:32 pm

America had the Indian Adoption Project and with Canada – they used ARENA

Eleanor Grant · April 22, 2012 at 1:35 pm

May I highly recommend James Bartleman’s 2011 novel “As long as the Rivers Flow”. It tells of how a mother, a residential school survivor, struggles to pull herself together and then her scattered family. It ends with hard-won hope for the future. I hope Bartleman will keep writing.

Colleen Cardinal · April 22, 2012 at 4:13 pm

Thank you for writing such an important article, we see alot of articles about the Residential Schools & survivors but the 60 ‘s Scoop is just as important. There are thousands of Native adoptees all over Canada,Europe & the U.S who are searching for their families but also their identity.

Chad Rancher · April 22, 2012 at 9:38 pm

Your insights and sensitivity to the barbaric actions of sanctimonious and ethnocentric social service workers give a new and much needed message to the public that families need to be preserved. The damage flows from one generation on to the next into infinity. No higher power would ever want families torn apart simply because government agencies continued to promote the mistaken belief that First Nations’ parents did not deserve to raise their own flesh-and-blood children. The loss of one’s natural family, heritage and culture from forced adoption, residential schools, and foster care is a wound that never heals. How much more hurt and pain must be endured before the world finally wakes up from these systemic abuses? Thank you for writing this amazing article. Please continue all your wonderful efforts until everyone finally learns the truth.

Perry Bulwer · April 23, 2012 at 12:28 pm

Here are some excerpts from the written submission I gave to the TRC, which focused on this subject. I also expanded on this submission in my recorded oral interview.

******

“… It was shocking to me and broke my heart to learn of such secret abuses, some of which happened in my own backyard, so to speak. I began to wonder whether my own family had been deceived by the government to unknowingly take part in its assimilationist policies by adopting two Aboriginal children in the mid 1960s. My parents had no malicious intention in adopting Aboriginal children into a non-Aboriginal home. They were altruists, with two children of their own, who simply wanted to provide a home to two other children who had none. But what I do not know, as I was only around 10 years old at the time, is how much they were aware of the history of residential schools and how the accelerated mass removal of Aboriginal children from their families and communities into the child welfare system in the 1960s, referred to by some as the Sixties Scoop, was an extension of the residential school system. I also do not know whether or not they were encouraged, pressured or manipulated by government agents, such as social workers, to specifically adopt Aboriginal children, though I do suspect that based on tactics used at the time to coerce unwed mothers to give up their children, as pending class-action lawsuits allege. That is a conversation I have not yet had with my parents, but I mention that here as a different example of the far-reaching effects of the government’s policies towards the First Nations. It troubles me deeply that the government, whether directly or indirectly, may have involved my non-Aboriginal family in a program that violated the basic human rights of so many Aboriginal children and their families. Racism is abhorrent to me, state sponsored racism even more so.

“Please do not misunderstand me. I am glad that my parents adopted my brother and one of my sisters, or else there is a good chance they would have bounced from foster home to foster home, or suffered in institutionalized care, as so many other Aboriginal children did who were removed from their parents under questionable circumstances. I am just sad and mad that government policies created the circumstances that made it necessary, that those little babies had to grow up away from their natural families and outside of their communities and cultures. At least my parents tried to expose them to their Aboriginal heritage, which is why I am convinced they adopted for altruistic reasons rather than as a consciously deliberate act to further the government’s agenda. So now, for my brother and sister, my nephews and nieces, and their children’s children’s children, I do my small part to fight racism where ever I encounter it, to educate others on Aboriginal issues and rights, and to stand in solidarity with the First Peoples.

“After I graduated from VIU in 1996, I moved to Vancouver to teach, but after a few years entered law school at UBC in 1999. I was particularly interested in both social justice issues and Aboriginal law so took several courses in that area. I also worked at the UBC First Nations Legal Clinic in the Downtown East-side of Vancouver for eight months, first for a semester credit, and then for four months as a paid summer job. On that job I encountered many of the long-standing, inter-generational health, social, and legal issues caused directly or indirectly by the residential school system. During that period, I was also involved in voluntary advocacy for the rights of street sex workers in my East-side neighbourhood. This was at a time when many women were disappearing off the streets of Vancouver and their serial killer had not yet been found. Many of the missing women were Aboriginals. It was a heart-breaking situation, and the authorities did not seem to care.

“I am very familiar with that case because I lived in the neighbourhood where many of the victims were working and disappearing from, and know all too well the disdain many police officers had for street prostitutes and their advocates. …

“While the police were still in denial that a serial killer was preying on vulnerable street workers, until he was finally arrested in 2002, those street workers and their advocates had every reason to believe the police were denying the obvious because of who the missing women were. That seems even more obvious today. While I was in the midst of drafting this submission, the media reported that the independent lawyer representing the interests of Aboriginals at the Missing Women Inquiry has resigned, condemning the hearings for failing to listen to marginalized people. She stated: “This inquiry is fundamentally about missing and murdered women, a disproportionate number of whom were Aboriginal. …

“My family is a microcosm of the three founding nations of Canada. My father’s heritage is English, my mother’s is French, and my brother and sister’s is Aboriginal. When my siblings or their children are the subject or target of racism, I take it personally as an attack on me and my family. Similarly, when ignorant bigots denigrate Aboriginal people in general, I take it personally as an attack on my Canadian identity. Racism has defaced that identity, and the scar will remain as a reminder of that ugliness, but I remain hopeful that together we can eventually erase racism from the body politic. To that end, I attempt to fight back against racism where ever I encounter it, whether online or in the real world, by exposing false stereotypes with facts and knowledge. It is my small way to further the goals of truth-telling and reconciliation. … “

Vanessa McCourt · April 24, 2012 at 8:33 am

Nia:wen (Thank-you) Perry for your honesty. Your words inspire me to do more.

Vanessa

Kiaayohkats · April 25, 2012 at 3:51 am

And it’s still going on.

“[Between 1979 and 2004], the PERCENTAGE of Indian children taken into care has doubled. In the same period, number of adoptions has increased by a factor of five, while the proportion being adopted by non-Indians has grown from 50 percent to about 80 percent; put another way, eight times as many Indian children are now lost to the Indian community as formerly. This has been explained largely on the basis that these children are now living in BETTER MATERIAL AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS”

-R. Bruce Morrison and C. Roderick Wilson, Native Peoples: The Canadian Experience, 2004:454

The ethnocentrism embedded in these conceptions of “better material and social conditions” is sickening. Really, it’s just another wave of assimilation. While, as noted, our children are “integrated” in “white, middle-class homes in white, middle-class neighbourhoods”, our families and communities find themselves further degenerated and our ability to transmit our culture is threatened.

sharilee · April 20, 2013 at 11:44 pm

This was a shameful period of Canada’s history, and needs to be addressed by the Federal government.

Shelby LePage · May 2, 2013 at 8:32 pm

http://missteensouthernbritishcolumbia.com/

I wanted to share my blog with you, I just finished the “We Stand Together” campaign bringing awareness to Aboriginal Culture, History & Traditions!

Todd Giihlgiigaa DeVries · May 9, 2013 at 1:25 am

Assimilation is practically complete. How many people, live traditionally from the land, with no electricity, plumbing or gas? Nowadays, camping is likened to “inadequate housing.” Try earthbag buildings, as they look like “real” buildings but cost 1/100th of a wooden house (wood rots in 15-20 years). Earthbag, like adobe, lasts for centuries, costing less than a $1000 in materials. Who wildcrafts harvests, or hunts nowadays… community harvesting and farming? The 60’s scoop, residential school took away all hope when they took the children, and any hope of getting help. Government says the natives are poor, but the natives are rich in land that generate unlimited income, as compared to selling it for a couple of thousand dollars, and then have nothing to feed oneself once the couple of thousand dollars have been spent…. crazy reverse psychology, and many people believe it….

âpihtawikosisân · May 9, 2013 at 8:00 pm

Sounds like you may need to read this article to help cope with the issue of what is traditional:https://apihtawikosisan.com/2012/01/14/the-that-isnt-traditional-meme/

As for the issue of land, it is indeed ridiculous to expect that the one third of reserve lands that actually remain in First Nation hands after two thirds were lost to encroachment and theft would be something that FNs would willingly give up for a few dollars now, with nothing for future generations. It is also ridiculous that Canada so desperately wants that half of one per cent of land south of the 60th parallel that is still reserve land. Talk about greedy!

Virginia June · September 7, 2013 at 8:36 am

I have taken back my cultural heritage even in the face that my grandparents were adopted out and raised as “white.” My great grandmother died in childbirth, both my grandfather and his 3 year old sister were separated and raised white. All I know of my great grandmother is that she was Iroquois and her name was “Ona.” My grandfather married a metis woman that was Shoshone and French Canadian. My father married an Irish woman and we were raised Irish Catholic. Alcoholism, and abuse run back generations. I grabbed my heritage on my father’s side, and the Spiritual connection that I obtained in lodge, vision, pipe etc. saved my life. I give immense gratitude to my ancestors! Adoption attempts to kill the vision…but the vision does not die! Ho!

Amanda F · March 12, 2015 at 12:12 pm

The ‘Adoptees themselves’ link is broken, I think the article was removed, but I’m very interested to read any information about what people have to say about their experience and loss..

âpihtawikosisân · March 12, 2015 at 12:29 pm

Thanks for the heads up, I have fixed the link, which is to an CBC 8th Fire documentary: Hidden colonial legacy, the 60s scoop.

David · May 17, 2016 at 6:22 pm

I was brought up in a foster home in the early 60’s to early 70’s, as a male child I was physically abused, and the girls raped!!! We thought the was the way of the world as we were told we were there because nobody wanted us… Well I am 57, been through 2 marriages and many relationships, I am an alcoholic, cant hold a job, because I was told I would never amount to anything, I hear all the stories on our aboriginal foster kids who had it so tough, let me tell you I could tell you true stories that would fuck up your head, compared to them.. And what do I do?? I don’t know, I may go to jail in June because I Am fk’d up from that shit.. Never had true guidance, don’t know how to cope, Tried. always fell on my face, I get up but I keep falling down. So who the hell can help me?? Nobody cause nobody cares, There I said my piece, I hope somebody reads this because I have just about had it with all the nightmares even to this day, So someone tell me their life is tough.. whatever!!!!!!!

âpihtawikosisân · May 18, 2016 at 7:06 am

I am sorry for your experiences. Unfortunately many Indigenous foster kids have experienced as horrific situations. This is not about who had it worse…no child of any background should be abused, and that is the standard we should be reaching for.

John W. · January 5, 2018 at 3:12 pm

I was in foster care my whole life until I decided it was time to leave at 17. I did the jail thing the drug thing the drinking thing and guess what I finally found someone who I felt good with and married her and that was 28 years ago. I know I will never forget the nasty truth but I found that one thing that kept me going and maybe others find a hobby or something that keeps their mind from getting worse. I think the power of the mind can help but the honest truth you can’t ever forget you just have to find a way to move forward. I was in early 60’s swoop child at 3 months old taken away so you can’t take away a childhood and think you can get over it right? I hope to all who endured pain and suffering that you can or have found something or someone who helps you everyday.

Genevieve · May 12, 2022 at 4:37 pm

I was denied status I am so angry… I think there should be exceptions to this… And one of them should be children of parents in residential or and 60 scoop!

my mother has status I think it’s 6(2)and my grandma has status also… My father’s not on my birth certificate I was raised by my mother… And she was a child of the 60s scoop… She was Sexually abused and just abused… Because of this she was not a very good parent…I was horribly neglected abused there’s documentation of it… I feel that I deserve native status! I was denied…

Is feminism good or bad? · May 9, 2012 at 1:52 pm

[…] […]

The Femisphere: Bloggers From Canada · June 12, 2013 at 4:37 pm

[…] The Stolen Generations(s) […]

We can’t get anywhere until we flip the narrative » Delusions of Development · August 22, 2013 at 11:39 pm

[…] In July, a Calgary Herald journalist Karin Klassen wrote an article which in essence, defends the 60s Scoop and suggests that First Nations people are culturally unfit to parent. This opinion piece was not […]

We can’t get anywhere until we flip the narrative | Declaration of Indigenous Rights · September 5, 2013 at 1:56 pm

[…] In July, a Calgary Herald journalist Karin Klassen wrote an article which in essence, defends the 60s Scoop and suggests that First Nations people are culturally unfit to parent. This opinion piece was not […]

First Nations Won’t ‘Get Over’ Your Ignorance | Declaration of Indigenous Rights · September 6, 2013 at 1:29 pm

[…] In July, Calgary Herald journalist Karin Klassen wrote an article which, in essence, defends the ’60s scoop and suggests that First Nations people are culturally unfit to parent. This opinion piece was not […]

What Revolution Looks Like to Me | Declaration of Indigenous Rights · November 3, 2013 at 12:53 pm

[…] from their families and communities did not end with Residential School. It did not end with the sixties scoop, but continues today. In Manitoba, indigenous children make up 20 percent of the total child […]

Mrs. Ell's Research Essay | Pearltrees · February 8, 2016 at 4:53 pm

[…] It's estimated 20,000 native children across Canada were taken by provincial officials, after the provinces assumed responsibility for child protection services from the federal government in the 1960s, says Marilyn LeFrank. Children continued to be removed from their homes through the 1970s and as late as the 1980s. "Children were taken from their homes and adopted, many of them, in non-aboriginal homes, many of them in the United States, without parent consent and without a lot of paperwork in some occasions," said LeFrank. The Stolen Generation(s). […]

Truth and Reconciliation | Gasoline Gypsy · June 21, 2016 at 11:02 pm

[…] a class action law suit by Klein Lyons firm for Aboriginal kids who had been part of the “60s Scoop.” These were children who were removed from their families and placed into foster care, […]

Grassy Narrows First Nation & Aboriginal Issues in Canada – McGill Blog and Stuff · August 17, 2016 at 11:13 am

[…] I’ve always been amazed with the ignorance and the slackitivsm of non-Indigenous in Canada (particularly Caucasian ones) when it comes to Indigenous issues. Whether it’s the should’ve-been-decades-in-progress Truth and Reconciliation Report or the time it took a Canadian federal government to sit down with the National Chiefs and discuss actual pertinent issues (see video below), Canada as a whole is far behind in the push for equality of all its citizens. However, it can definitely be agreed upon that this recent push was far bigger then had ever been accomplished, and ironically, this push was from yet another Trudeau, almost a quarter of a century later with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (although Trudeau Sr’s efforts towards Indigenous rights have been, in simplest terms, largely contested). […]

Teaching the Legacy of the Sixties Scoop and Addressing Ongoing Child Welfare Inequality in the Classroom – ActiveHistory.ca · February 27, 2017 at 7:01 am

[…] same cannot be said for the sixties scoop. While discussing residential schools and colonial relationships in Canada I often discuss other […]

Anarchist news from 300+ collectives 🏴 AnarchistFederation.net · June 25, 2021 at 1:00 pm

[…] himself as “a product of foster homes,” Cardinal was part of the “stolen generations” or 60s Scoop, a term that refers to the estimated 20,000 Indigenous children taken from their families between […]

We are facing a settler colonial crisis, not an Indigenous identity crisis - INS News · January 26, 2022 at 10:11 am

[…] work that often focuses on healing intergenerational divides caused by Indian Residential Schools and the 60s Scoop — but this idea of “re-indigenization” was […]