The Inuit make no bones about it. Theirs is a hunting culture; but what does that mean?

Most Inuit still eat a solid diet of country food, which is just like it sounds, traditional foods such as caribou, whale, seal, fish and so on. Hunting remains a central practice in Inuit communities. So is that all it takes to be a hunting culture?

Actually going out and hunting is a pretty important part of a hunting culture, but the act itself is not everything. The focus on hunting informs the language, the traditions, the stories, the music, the art.

The hunting theme can be found in every aspect of Inuit culture, especially art. Many of the tools and weapons used in the past were decorated with hunting images, as were objects used by shamans. Many stories revolve around hunting. Alootook Ipellie, formerly of Iqaluit, Nunavut (now deceased), wrote that so many Inuit are good carvers because “they come from a very visual culture. Their very livelihood depended solely on dealing with the landscape every day during hunting or gathering expeditions. They were always visualizing animals in their thoughts as they searched the land, waters, and skies for game” (1998:97).

2009 bowhead whale hunt in Nunavik. All but two communities participated and all communities shared in the bounty.

Culture informs our interactions with the world around and inside of us. It informs our pedagogy. When you look at some of the principles of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit (IQ), which is traditional Inuit knowledge, it is not difficult to see how these principles have been shaped by hunting. It should also not be so difficult to see how these traditions are absolutely applicable to the modern era:

- Inuuqatigiitsiarniq: concept of respecting others, relationships and caring for people.

- Tunnganarniq: concept of fostering good spirit by being open, welcoming and inclusive.

- Pijitsirarniq: concept of serving and providing for family/community.

- Aajiiqatigiingniq: decision making through discussion and consensus.

- Pilimmaksarniq: concept of skills and knowledge acquisition.

- Qanuqtuurungnarniq: concept of being resourceful to solve problems.

- Piliriqatigiingniq: concept of collaborative relationship or working together for a common purpose.

- Avatimik Kamattiarniq: concept of environmental stewardship.

As with other indigenous peoples, these hunting principles were eroded by the introduction of fur trapping.

Previously, work and profit had been shared among community members, but with the advent of trapping, hunters worked alone for a private income. In the early 1900s, posts were commonplace in most areas of the Arctic, as were guns and traplines. Their widespread use greatly changed northern practices as the trapping way of life was in direct conflict with the old way of hunting, which was done in groups with proceeds being shared.

New principles were introduced, and had a profound effect on Inuit relationships with one another, and with the land. Nonetheless, when modern Inuit articulate foundational cultural principles and apply them to present-day issues of governance, law, pedagogy, and so on, they do so within the framework of the “Inuit Way” which continues to be rooted in a hunting culture, not a trapping culture.

Is the difference between hunting and trapping at all important?

Yes, and no. Yes, in that trapping is an activity that is focused on the individual, commercial aspect of one particular form of hunting. As discussed above, trapping tends to be an activity that is more individual, rather than collective. The values of a hunting culture are not necessarily the same as the values of a trapping culture.

That is not to say that trapping must be incompatible with values such as those expressed through Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit or other indigenous peoples’ principles. The ethnogenesis of the Métis for example, is inextricably linked to the fur trade, yet our collective values are not so widely divergent than those of our First Nations relations. Commercial transactions between indigenous nations were happening long before Contact with Europeans, and so the commercial nature of trapping does not automatically render it ‘un-traditional’.

An estimated 25,000 indigenous people continue to participate in the fur trade through trapping though anti-fur campaigns have put a serious dent in the industry.

However, if trapping is just one of a range of the broader category of ‘harvesting’ activities, then the difference may not be important at all. Indigenous peoples ‘trapped’ fur-bearing animals before the fur trade, though never as an end in itself. It can be viewed as just another hunting practice.

The way in which the Canadian state treats hunting versus trapping is important to examine. In Treaty 8 territory, for example, Alberta treats trapping as a purely commercial right and “regulates it accordingly“. Blanket trapping regulations are applied to native trappers, on the basis that commercial rights under Treaty 8 were extinguished by the Natural Resource Transfer Agreement. Licensing, fees, quotas, regulations about the building of cabins for trapping and so on are all applied to aboriginal trappers. In addition, trapping is often seen as a ‘weak right’ to land in comparison to hunting.

Worse, Peter Hutchins points out that “the very existence of traplines has been used to deny the survival of aboriginal rights or titles” based on the notion that traplines are a form of individual tenure extinguishing collective aboriginal or treaty rights.

So what is going on here?

In essence, there are indeed two views of what trapping is. Canada tends to take the view that trapping is an imported, specific activity that is different from aboriginal hunting in that it is individual and commercial in nature, not rooted in indigeneity. Most indigenous peoples see trapping as a subset of hunting, which is itself integral to our cultures.

Cree trappers, or Cree hunters?

This ‘subset of hunting’ approach can be seen in practice by the Eastern James Bay Cree of Eeyou Istchee. Under the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement, provision was made for the creation of a Cree Trapper Association (CTA).

Though the name and focus would seem to be on trapping alone:

one of the many goals of the CTA is to promote sales and assist in the orderly collection and marketing of wild furs by its 5000 members.

It is also very clear that as envisioned by the CTA, trapping is an integral part of the collective culture of the Crees of Eeyou Istchee:

The role of the Cree Trappers’ Association is an important one, it is to protect and maintain a way of life that completely identifies who we really are as Eeouch who depend and continue to depend on the land for survival.

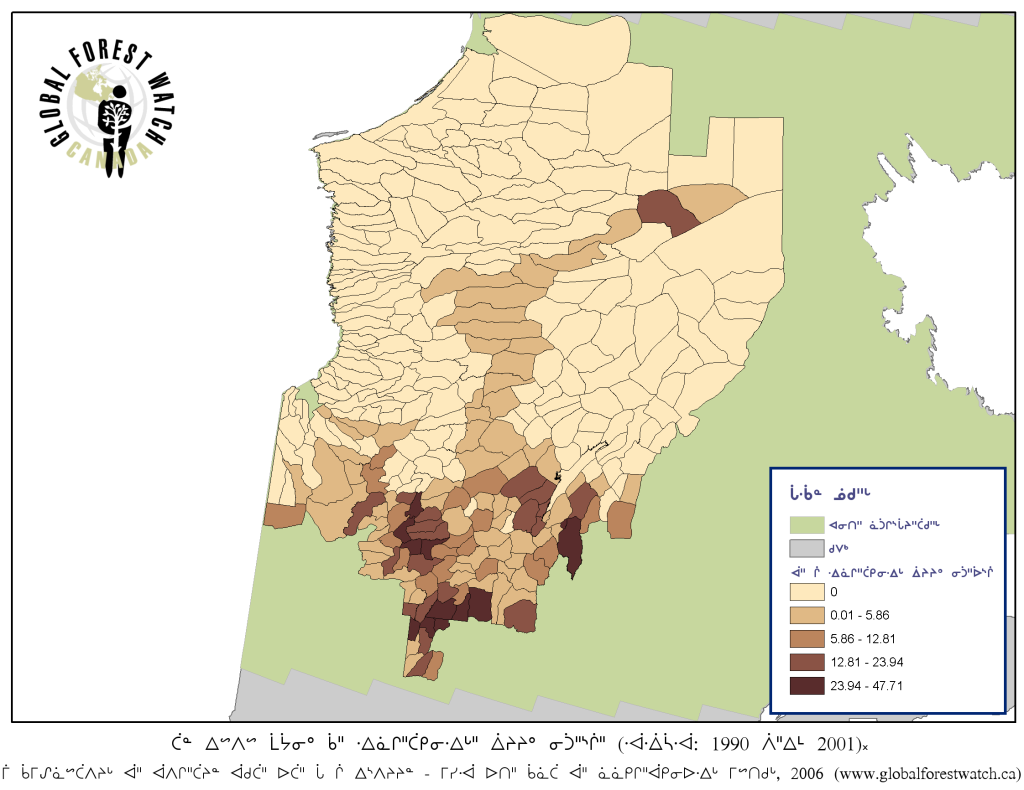

The Grand Council of the Crees (GCC) have a heck of a lot nicer maps detailing these territories, but this gives you a sense of what Eeyou Istchee (Eastern James Bay Cree territory) looks like divided into traditional family territories.

In addition, the CTA and its members are guided by the Eeyou Indoh-hoh Weeshou-Wehwun, the traditional Cree hunting law. The trapping of fur bearing animals is treated as a subset of this wider Cree hunting law, all of it a part of Indoh-hoh (harvesting activities).

What is most interesting to me is the difference between the Cree and the English in this situation. That super cool map above, when referred to in English, shows trapping territories. According to customary law, each trapping territory has a tallyman, who is in charge of managing the resources within his territory. The name ‘tallyman’ is defined in various pieces of legislation applying to the Eastern James Bay Cree as “a Cree person recognized by a Cree community as responsible for the supervision of the activities related to the exercising of the right to harvest on a Cree trapline”.

The Cree of Eeyou Istchee use the central symbol of a hide on a stretcher in most of their organisations, giving one a sense of just how important hunting and trapping is to the Cree culture.

Originally of course, the tallymen tallied up furs for the fur trader. The informal Cree word for this person is ouchimaw (in my dialect it’s okimâw) often translated as chief, or boss. Someone put in a position of authority over something, in this case, the management of the land. The job of the ouchimaw is not just to keep an eye on trapping in his territory, but rather to ensure the health of the territory as a whole. The formal title for a tallyman is Kaanoowapmaakin, which can be translated as hunting leader.

In Cree, the map above shows the Indoh-hoh Istchee, the traditional hunting territories as defined by Cree traditional law. Indoh-hoh wun are all the animals within one of these territories, not just the fur bearing ones.

If you look on page 17 of the document detailing traditional Cree hunting law, you will find that the responsibilities of a Kaanoowapmaakin in his or her traditional Indoh-hoh Istchee goes far beyond what you might envision a head trapper doing. The responsibility is not just to individual trappers, but to all Cree people and all living things within Cree territory. The Kaanoowapmaakin must monitor, manage, and share resources within his or her territory. His or her authority extends to resolving territorial disputes, inviting guests into the territory and so on.

So while the English terms focused on trapping as an imported, individual economic activity, the Cree terms make it clear that trapping is a part of a wider hunting culture which is governed by traditional laws and is central to the Cree culture.

All very cool, but where is this going?

I am not drawing you towards some stunning conclusion, I am merely drawing you towards the question itself. Does it matter what the Canadian government calls us?

I am of the opinion that it does. When the terms used are English ones, defined in English and seen through the colonial lens, much is lost. If some of our hunting activities are being defined as ‘trapping’ and this definition results in the erosion of our indigenous rights, which has indeed been the case, then it is important for us to challenge these terms.

The Cree Geo Portal is an absolutely amazing use of technology as applied to traditional Cree land management. You should spend time nosing around!

Rather than seeking better English or French translations for indigenous concepts, I feel it is important to return to our languages for the proper terms. In this way, we center ourselves in our traditional laws and our traditional understandings of the reciprocal obligations we have to our territories and to one another. Far from being feel-good back to nature, yearning for pre-Contact mumbo jumbo, our legal principles are foundational and applicable to the modern era.

Most of the Eastern James Bay Cree communities in Quebec have shed their English and French names in favour of Cree names, and chaos did not ensue. I think that indigenous resurgence is very much rooted in the use of indigenous languages. Canadians in general, individually and collectively, must become more accustomed to forgoing facile translations in favour of delving into the complexities of our indigenous principles. To be honest, we could all benefit from doing this more often.

I’m interested in what you have to say on the subject. How much does language matter? How much do these terms matter? Do you think that the language used is a vehicle for the erosion of rights? Can it be a vehicle for the assertion of rights?

Alright, I’m going to go back to the Cree Geo Portal and check out even more awesome resources.

22 Comments

Leslie Robinson · March 4, 2013 at 4:57 pm

Very interesting. Thank you! I’m glad I found your blog; it’s a learning opportunity for me.

ourstudycorner · March 4, 2013 at 5:10 pm

I feel I must tell you a smiling story. When my husband and I were first together, he frequently would ask me to go and get the neehee. Sometimes that neehee was on the nawhaw. At this point in my story, I need to explain that my husband was Ojibwa and I was non-Native. Now try as I might I could never figure out the meaning of those words because they seemed to keep changing. Sometimes he wanted me to get his smokes and another time his hammer. It just did not fit, but I was too embarrassed with obvious ignorance to ask for the meanings. Finally I asked a relative and she laughed and laughed as she explained that it was like my saying the whatchamacallit and the thingmajig. You are doing amazing work. I just thought you needed a smile today.

susanhughesspencer · March 5, 2013 at 8:15 am

What a wonderful “smiling story”! It certainly made me smile. Thanks!

Siusaidh · March 5, 2013 at 12:13 pm

Those Ojibs – such a lot of kidders. Thanks for a chuckle.

Chris Corrigan · March 4, 2013 at 6:17 pm

Years ago when I was studying what was then Native Studies at Trent University, a fellow third year and I wrote a paper that looked at how Cree hunters negotiated the JBNQA. We went to McGill and combed through a bunch of interviews that McGill researchers did with the negotiators in the early 1970s and what we saw was really cool. The negotiators treated the treaty as they would any other hunt. They dreamed the settlement they wanted and it was tied to what they knew of the communities’ needs. They approached the work as they would approach anything that provided for the well being of their families. When they went south to Montreal to negotiate they did so the only way they knew how, which by dreaming what it would be like to be there, and by recognizing those situations when the encountered them.

It was a profoundly important piece of work for me to see that traditional and indigenous views of the world have a place in working with and solving contemporary problems. It has informed my belief and work in supporting traditional learning for the past 25 years. And so, this mindset is actually absolutely critical to the assertion and practices that support Aboriginal title and rights.

And they are also just darn effective ways of getting things done!

nmr · March 4, 2013 at 7:27 pm

Have environmental toxins affected the hunting culture? I am thinking in particular or the Faroe Islanders who are now dissuaded from hunting pilot whales because of the high levels of mercury, PCBs and DDT in the whale blubber.

âpihtawikosisân · March 4, 2013 at 7:44 pm

It is definitely having a negative impact. When I lived in Inuvik, the community nurses warned me not to eat too much fish while I was pregnant or breastfeeding. I was told that environmental toxins have become concentrated in the Arctic because of the way the currents work (I’d have to seriously refresh my understanding of this to explain it better), and because many of these toxins are fat soluble, those that rely heavily on food from the oceans are getting high doses of mercury and other pollutants. This is a know issue with fish in general, but is particularly bad for the Inuit who rely so much on whale, seal, and ocean fish. But what can people do? These are not the ones dumping this into the ocean, and yet they face some of the worst effects from it.

It is not limited to the oceans. I would not eat deer, moose or elk from around my territory. Too many hunters have found abscesses in game, and bad growths. The meat often smells bad, sometimes the organs are shrunken, wrong. We haven’t been able to eat the fish out of our lake since I was a child, and even then it probably wasn’t safe. You have to go further and further away to find healthy animals…but then you start running into the same problem as you go up further North. The North is used as a garbage dump for radioactive tailings, industrial pollutants and so on, impacting the aquifers, the ground water, the animals, and the humans that rely on them. When you don’t get your food directly from the land, it is easy to not know any of this is happening.

Bruce Weaver · March 5, 2013 at 9:42 am

Excellent points. When we lived in Tikirijuaq (Whale Cove) in 1971, the whaling station had been closed for several years because of mercury coming up from teh prairies where it is used to keep seed from rotting. Seal meat was also problematic. Everyone ate char and we have no idea how they were affected.

Miranda Paymer · March 4, 2013 at 7:31 pm

How much does language matter? Hugely! A culture’s language is formed by the culture AND it forms the culture (psycholinguistics). How a person in a culture can communicate, and how they can think (at least as adults), are based on the concepts the language allows and disallows. As an Army brat, we were stationed where I, as an infant initially, learned English and German together. These are very related languages, yet trying to translate some concepts from one to the other doesn’t really work. When dealing with languages more disparate in origin, that ‘translation’ issue becomes very significant. No one can truly understand another culture unless they are fluent in the language. Killing the language, as many Europeans when the Americas were “discovered,” was an important way of killing the culture.

Brian · March 4, 2013 at 11:25 pm

I have a friend who is becoming an Anishinaabe/Algonquin speaker. He explained to me that the names of trees, plants and other natural things refer to how the are needed and used by the people. Without that language so many understandings about how to live on the land would be lost.

âpihtawikosisân · March 5, 2013 at 9:53 am

To add to that, learning the place names of the territory you are in goes a long way to uncovering the history of the area, as many names refer not only to natural landmarks but important events.

Bruce Weaver · March 5, 2013 at 9:44 am

This is another excellent article. One that makes me more determined to learn more about the Haudonosee

Brenda · March 6, 2013 at 11:55 pm

I may be naive in my thoughts, but here’s what I want to say. Native cultures in North America, before the onslaught of Europeans, were hunters. They hunted for the good of their own particular communities. Furs and skins, and bones, being a by product of hunting for meat, were used within the communities for clothing and warmth and tools. The influx of Europeans, wanting just the furs, (and trading furs for previously unnecessary European goods), put a different pressure on Native communities. And it put a big negative pressure on the animal populations. As I understand things, hunters and their families had ceremonies to honour and respect the animals who gave their lives so the community could survive. The people took only what they needed, and they used every little bit of the animals who gave their lives for them. I think the European pressure for furs changed things within the Native communities. The Natives started killing animals just for their skins, and trade these skins for things they really didn’t need in their already perfect world. I think this so changed the spiritual understandings between man and animal, the trust and respect that had been in place for many thousands of years.

I know, the world has changed. Everything is changing. I so wish we could all just go back a thousand years and live in PEACE with our Other Mother.

Cathy Caccavella · March 12, 2013 at 3:03 pm

Exact definitions of words are absolutely integral to the delineation of identity, activity and possession, and continued survival. The redefinition of words, however covertly or slyly done leads as you have so ably pointed out in your article to the abdication of freedoms. And all it took was a slightly altered definition of an activity and skill inherent in First Nation culture.

Thank you for a well thought out article, and I hope it prompts others to take a careful look at exactly how change is being accomplished in Canada. The skills of the First Nation people, their language and art is not just an expression of culture but of a universe that encompasses not only a sector of humanity but all the life forms and patterns of existence within that universe.

Four hundred years ago Europeans confronted a wealthy people who existed in a far different condition than is current. An examination of that decline could possibly be useful in reversing a trend that may seem economically expedient but which continues to endanger the existence of what will someday be regarded as a great civilization, fully in command of its environment, and existing in harmony with it.

michaelwatsonvt · March 17, 2013 at 9:43 am

Wow! You have done your homework! Thanks for this thorough, insightful post.

madravenspeak · March 25, 2013 at 12:19 am

I wonder if you have considered, given the times, the overpopulation of humans and the rapidly declining wildlife populations world wide, dying overkilled oceans, that the earth is calling an ancient call for respect for all beings and the animals having their lives respected for themselves and their own rights – rather than the ancient utilitarian concept of all life as something to enable human life. The indigenous people from all over the world are leading in their drafting of the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth and All Beings. The first right of all beings is to EXIST. Secondly, not to be harmed by man. Thirdly, not to be incarcerated by man but to live out their lives in the natural world contributing their lives in the natural circle of life.

We have learned a lot about humans and their rationales for killing each other and other beings. Man has valued his own “reason” to separate himself in an artificial hierarchy of lording it over all beings and deciding their fates. Indians have been no better in this regard – and seem to have become more abusive. There is no other species on earth that seeks to separate him/herself from all life as humans do in some oligarchic rapture of control and entitlement.

Sorry – the right to kill other species has brought us to this brink of killing off our own world. 55 billion livestock for slaughter, spearing, trolling, finning, whaling, trapping ( OBSCENITY of cruelty), and killing with every weapon from low to high tech.

It is time for a new wildlife ethic – beyond ancient indigenous cultures. We are in a new age calling for a new ethic of reverence for all life and a plant based healthy diet or we lose our planet forever. Animal agriculture is 51% of global climate change, and hunting is wiping out wildlife in trophy and fun and food killing across the world.

It is time for an ethic of reverence for all life. It is time for us to turn our attention with love and respect to help other creatures and stop causing them suffering and rationalizing killing.

âpihtawikosisân · March 25, 2013 at 6:26 pm

Ah yes. Indigenous peoples are the ones who have hunted animals to extinction, who have decimated the fisheries, and who farm animals for their fur and flesh. Thank you for so eloquently pointing out why many animal rights activists are considered just another breed of colonially-minded antagonists, too lazy to actually learn anything about us.

For animal rights without the ahistoric spin, I recommend The Fruitlands: http://thefruitlands.com/

Hint, you will have to look up the term ‘intersectional’ before reading.

madravenspeak · March 25, 2013 at 12:24 am

http://pwccc.wordpress.com/programa/ This is the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth and All Beings to balance the Declaration of Human Rights. It was drafted by a South African lawyer, Cormac Cullinan, with input from indigenous people from all over the world at the Cochabamba, Bolivian climate conference in 2010. It was presented to the United Nations in 2011. It was put into the constitutions of both Ecuador and Bolivia in 2012. Third world countries are leading the way to save biodiversity and our climate.

Out with the old rationales for killing – there is no going backwards.

âpihtawikosisân · March 25, 2013 at 6:28 pm

I think it’s hilarious you quote something you apparently have no actual understanding of, what with your last silly rant against ‘ancient indigenous cultures’.

Chelsea · April 18, 2013 at 8:07 pm

I think that they deserve respect. They respected nature much better then we did.

Bev Jo · September 24, 2013 at 1:48 pm

I agree, âpihtawikosisân — “many animal rights activists are considered just another breed of colonially-minded antagonists, too lazy to actually learn anything about us.” I’ve seen vegans bully more oppressed peoples for decades. It’s extremely dangerous for humans to believe themselves to be outside of nature, above other animals, and that somehow their arrogant superiority will protect them from needing the nutrition our omnivore type of animal body obviously must have to be healthy. Yet they pretend to care for other animals. I appreciate Lierre Keith’s “The Vegetarian Myth” in talking about all this.

Indigenous hunter/gatherers are clearly the cultures who harm the earth the least and who must live in harmony for survival. Most vegans have carnivorous animals they either feed meat to or starve, but they should learn from the animals they love. Trying to police the cultures of the people who have harmed the earth the least is typical colonialst racism and often classism too.

Loving and respecting animals seems to be more part of Indigenous hunter/gatherers than any other peoples.

Animal Activists Outraged at Canadian Seal Meat Burger - The Burger Nerd · October 16, 2013 at 9:30 pm

[…] They are simply utilizing a small amount of seal meat to feed people. Which is the same thing many Inuit still do, the same thing countless people do with other animals, and the same thing humans have […]