Recently a grad student in journalism at Concordia University contacted me to ask a few questions about the state of drinking water in First Nations communities. I’d been meaning to eventually write a piece on the issue, but her shock at what she had been learning reminded me yet again that many Canadians are totally unaware of conditions that most native people are all-too familiar with.

Chief Hector Shorting showcases some of the supposedly ‘drinkable’ tap water in Little Saskatchewan First Nation in Manitoba.

The term ‘potable water’ is often used when discussing various water purification initiatives in other countries. I think it’s safe to say that most Canadians would feel that potable water is a settled issue in this country, and that every person living here has (and should have) clean drinking water. Unfortunately, such is not the case for thousands of indigenous people. One of Canada’s dirty secrets is just how bad the water situation is, and has been, for so many aboriginal communities.

Let us first take a look at the Canadian Drinking Water Guidelines, put out by Health Canada:

Canadian drinking water supplies are generally of excellent quality. However, water in nature is never “pure.” It picks up bits and pieces of everything it comes into contact with, including minerals, silt, vegetation, fertilizers, and agricultural run-off. While most of these substances are harmless, some may pose a health risk. To address this risk, Health Canada works with the provincial and territorial governments to develop guidelines that set out the maximum acceptable concentrations of these substances in drinking water. These drinking water guidelines are designed to protect the health of the most vulnerable members of society, such as children and the elderly. The guidelines set out the basic parameters that every water system should strive to achieve in order to provide the cleanest, safest and most reliable drinking water possible.

Thus, ‘clean’ in relation to water is quantifiable. Note that while Health Canada in its federal capacity issues guidelines and procedural documents, the ultimate responsibility for water safety lies in the hands of the provincial and territorial governments. This of course makes it more difficult to get a sense of what is going on with water supplies in Canada. In addition, First Nations are a federal concern, and sometimes so are the Inuit. (The federal government has long denied responsibility for Métis, in case you were wondering.) I point this out so that you understand the following discussion is not going to be as clear, or simple, as you may have hoped.

What is a water advisory?

According to the Health Canada there are basically two types of water advisories:

Boil Water Advisory (BWA): An advisory issued to the public when the water in a community’s water system is contaminated with faecal pollution indicator organisms (such as Escherichia coli) or when water quality is questionable due to operational deficiencies (such as inadequate chlorine residual). Under these circumstances, bringing the water to a rolling boil for at least one minute will render it safe for human consumption (Health Canada, 2008a).

Boil Water Advisory (BWA): An advisory issued to the public when the water in a community’s water system is contaminated with faecal pollution indicator organisms (such as Escherichia coli) or when water quality is questionable due to operational deficiencies (such as inadequate chlorine residual). Under these circumstances, bringing the water to a rolling boil for at least one minute will render it safe for human consumption (Health Canada, 2008a).- Do Not Consume Advisory: An advisory issued to the public when the water in a community’s water system contains a contaminant, such as a chemical, that cannot be removed from the water by boiling (Health Canada, 2008a).

The Snapshot

Water advisories are not limited to First Nations. At any given time there are upwards of 1400 water advisories issued throughout Canada. Water security in this country is something that should concern everyone. Nonetheless, the severity and duration of water advisories in First Nations communities is nothing short of scandalous.

Health Canada reports that as of September 30, 2012, there were 116 First Nations communities across Canada under a Drinking Water Advisory. That is nearly 20% of all First Nations communities. This number has stayed pretty steady over the years. Between 1995 and 2007, one quarter of all of water advisories in First Nations lasted longer than a year. Sixty-five percent of these ‘long-duration’ water advisories lasted more than two years. One of the reserves I grew up by, the Alexis Nakota Sioux First Nation, has been on a boil water advisory since 2007.

Another aspect of this problem is the fact that some First Nations do not have running water at all, and thus are not counted when water advisories are tallied. In Manitoba alone, 10% of First Nations have no water service. Across Canada, there are 1,800 reserve homes lacking water service and 1,777 homes lacking sewage service.

Since water advisories can be lifted if conditions improve even temporarily, a community can have the same water advisory in place for an extended period of time or may experience a series of advisories without the situation truly improving much. Neskantaga First Nation, bordering the Ring of Fire in Northern Ontario has been on a boil water advisory since 1995. You can read about that community as well as five others in this Polaris Institute publication, Boiling Point.

Information is hard to come by

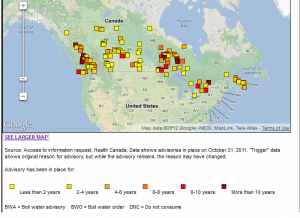

In 2011, Global News published an interactive map showing all the water advisories in First Nations communities at that time, as well as the duration of those advisories. The article accompanying this map does an excellent job of describing the nature of water advisories.

Note that in order to create this map, Global News had to submit an Access to Information request. That is because although Health Canada does keep track of water advisories that are issued throughout Canada, it does not provide a list that is available to the public. The only way to find out if there is a water advisory in place is to track media releases or find out after the fact through Access to Information.

Or that would be the only way, if it weren’t for the Water Chronicles, which tracks water advisories across the country and publishes them in an interactive map. The Water Chronicles divides water advisories into four categories: do not consume, boil water, water shortage and cyanobacteria bloom. Why we have to count on a volunteer research group to monitor this situation on a national level for us instead of having the information consolidated on the Health Canada site, I cannot fathom.

Why is potable water out of reach for so many First Nations communities?

Hopefully right now you’re asking yourself, how is this even possible? Well, the issue has been studied intensively. In 2005, the Auditor General of Canada issued a report on drinking water in First Nations communities. Basically, here’s how it works:

- AANDC provides the funds for designing, constructing and maintaining water systems in First Nations.

- Health Canada helps monitor water quality.

- First Nations are responsible for getting the construction done and the maintenance in place.

“Aha!” you say, “so if people still don’t have clean drinking water in First Nations communities, it’s because the leaders are corrupt and stole the money and didn’t build anything properly!”

Well dear reader of the National Post or Globe and Mail, it’s not that simple at all. The Auditor General identified a number of problem areas:

- No laws and regulations governing the provision of drinking water in First Nations communities, unlike other communities.

- The design, construction, operation, and maintenance of many water systems is still deficient.

- The technical help available to First Nations to support and develop their capacity to deliver safe drinking water is fragmented.

It is AANDC who defines the construction codes and standards applicable to the design and construction of water systems in First Nations communities, and the Auditor General found that these codes and standards are extremely inconsistent and poorly followed up on. In addition, the AG found that water testing by Health Canada is also inconsistent, hampering the ability to detect problems in water quality before a crisis arises. Added to this, most of those operating water treatment plant operators in First Nations are not properly trained for their position.

What has to happen?

Improving access to potable water for indigenous peoples in Canada is going to require cooperation and commitment.

This is not a problem that can be solved with a one-pronged approach. More money without addressing the regulatory gap and without ensuring capacity within the communities to ensure successful and safe operation of water service facilities has not, and cannot work. Yet despite a 2007 report by the Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples saying basically the same thing, not enough progress has yet been made on these issues. If your question is, “what needs to happen?” then let’s review the Senate Committee’s recommendations:

RECOMMENDATION 1:

That the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development provide for a professional audit of water system facilities, as well as an independent needs assessment, with First Nations representation, of both the physical assets and human resource needs of individual First Nations communities in relation to the delivery of safe drinking water prior to the March 2008 expiration of the First Nations Water Management Strategy;

That, upon completion of the independent needs assessment, the Department dedicate the necessary funds to provide for all identified resource needs of First Nations communities in relation to the delivery of safe drinking water;

That a comprehensive plan for the allocation of monies from said funds be completed by June 2008; and

That, upon completion of the comprehensive plan, the Department provide a copy to this Committee and appear before it to report on its contents.

RECOMMENDATION 2:

That the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development undertake a comprehensive consultation process with First Nations communities and organizations regarding legislative options, including those set out in reports of the Expert Panel on Safe Drinking Water and the Assembly of First Nations, with a view to collaboratively developing such legislation.

Has any of that been done yet?

Access to and control of water is considered by many indigenous peoples to be one of the most important issues facing our communities today. Artist Jared OxDx Yazzie highlights this important resource in his shirt, Water Is Life.

In April of 2011, Neegan Burnside provided the independent needs assessment recommended by both the Auditor General and the Senate Committee, providing us finally with a more accurate view of what the situation is and what needs exist. Almost all First Nations participated in the study (97%). AANDC provided a Fact Sheet in July of 2011, laying out the summary of the report. Since people often focus on cost, here is what the report recommended:

Having assessed the risk level of each system, the contractor identified the financial cost to meet the department’s protocols for safe water and wastewater. The total estimated cost is $1.2 billion which includes, amongst other factors, the development of better management practices, improved operator training, increasing system capacity, and the construction of new infrastructure when required.

The contractor also projected the cost, over 10 years, of ensuring that water and wastewater systems for First Nations are able to grow with First Nation communities. Including the aforementioned $1.2 billion to meet the department’s current protocols, the contractor’s projections for the cost of new servicing is $4.7 billion.

Problems with proposed legislation

Bill S-11, the Safe Water for First Nations Act was introduced in May of 2010 , but the much-awaited federal legislation recommended by the Auditor General and the Senate Committee met with criticism for not having been produced with actual consultation with First Nations.

Bill-11 was replaced in February of this year with Bill s-8. Critics of this bill point out that there is no funding formula included and call it a ‘piecemeal’ approach that does not respect Aboriginal rights. The Canadian Environmental Law Association submitted a briefing note to the Senate Committee pointing out three problem areas with the proposed legislation:

- the bill does not respect constitutionally protected Aboriginal rights

- there is no long-term vision for First Nations water resource management

- First Nations governance structures are not being respected

A legal analysis of the Bill commissioned by the Assembly of First Nations raises similar concerns (and is an excellent summary of the whole issue really).

As the Ontario Native Women’s Association points out, there is still no mechanism in place to ensure that development of regulations related to water in First Nations is a joint process, rather than merely top-down one.

This relationship has to change if things are ever going to improve

The top-down approach reflected in this proposed legislation HAS. NOT. WORKED. The water crisis in First Nations communities is not some recent development, but rather a chronic problem which was caused in great part by the failure of the federal government to bring First Nations into this process as partners.

Anishinaabe women have been spearheading “water walks” to bring attention to the vital role water plays in human life. In many indigenous cultures, women are particularly tasked with the responsibility of caring for the water, and this tradition has not been forgotten.

For years Canada lacked a proper understanding of the scope of the problem, but that can no longer be used as an excuse. We now have the most comprehensive study ever done on the issue. We know where we need to go.

First Nations are working hard to develop a national strategy. Canadians and the Canadian government need to join this process. The need is pressing, and that cannot be forgotten. All Canadians need to be aware of the severity of the problem, and I would further ask that they stand with us as we ask to be consulted properly in any proposed solution.

Water security is an issue everyone living in this country faces, and access to clean drinking water has long been considered a basic human right. Guaranteeing that right is going to take a population becoming more informed on the issues and more vocal in its insistence that access to water not be sacrificed in the name of economic development. Building relationships with First Nations, Inuit and Métis is a vital part of developing a national strategy that works for everyone.

24 Comments

Beerock · November 8, 2012 at 2:11 pm

FYI, Bill S-8 was heard for second reading last Thursday in the House, and the intent is to send it to committee. So far the NDP and Liberals are asking the right questions – where is the money to construct, operate and train – and as of late there has been no satisfactory answer from the Government to the important funding question.

âpihtawikosisân · November 8, 2012 at 2:53 pm

I would be completely unsurprised if this bill ended up passing. More people need to be asking the right questions before another decade goes by and another Auditor General’s report lambasts the federal government for once again dropping the ball on this. All the good intentions in the world don’t satisfy the stated requirement of funding, and comprehensive planning, neither of which seems to actually be in the works. I’m so frustrated with the situation that I almost wish someone would table a bill proposing that it be made illegal to not have access to safe drinking water…such a useless and ridiculous bill would perhaps highlight the ineffective nature of aspirational legislation.

norm hayward · October 5, 2015 at 12:39 pm

im a little black foot myself how about we just solve the issue instead of placing blame and ok so give me the list of whats in the water at each site specifically and the flow rates for consumption needed. to start with and then site specific maps of each site with existing water controls and including waste maps for each. lets include site specific ground water flows and elevations.so we can design all necessary redemil truths so we get to fix it once permanently.it will be a easy thing to let our universities to get involved and the public if we can know the truth blame and rhetoric is useless .facts are what we need.

Kerri · November 8, 2012 at 2:15 pm

I am so glad that you write this blog! I’ve been an eager reader for about 6 months and I want you to know that I greatly appreciate your thoughtful, critical, progressive perspective 🙂

S.B. · November 8, 2012 at 2:23 pm

Thank you for this post. I appreciate your insight and I will be happy to share this with family, friends, and colleagues. I like that you have included tangible recommendations. It is important to highlight serious issues of concern, but it is productive and necessary to provide plausible steps toward a resolution. Please keep them coming.

Bruce McGilvery · November 8, 2012 at 3:08 pm

Wow, This is great post. Ayhay

Anu Sandhu Bhamra · November 8, 2012 at 4:22 pm

What an insightful post; thank you so much. Disgust overcame me when I read the scope of the problem, but I like the tone of the article and your recommendations on what needs to be done. It’s senseless to see our “leaders” tour the world, make relations, sign new treaties when they are miserably failing in providing the basics to its own people, especially the real owners of this land. Shame on them.

Charles · November 8, 2012 at 6:36 pm

I enjoy reading all of your posts and this one didn’t disappoint. However, I have to disagree with the title, somewhat. It should read “Dirty Water, No Secret” because it’s no secret that many First Nations have struggled for too long with unacceptable water. How many more AG reports, federal gov’t studies are needed; or, how many more times do we need Peter Mansbridge to talk about it on the National before this situation is corrected. I know many very competent & professional operators that are forced to try and make safe water for their communities with inadequate infrastructure.

Ignorance is no longer a defence!

âpihtawikosisân · November 8, 2012 at 6:42 pm

I agree that the information is out there…reams and reams of reports and news articles and so forth. I called it a secret however, because despite the informational glut…a great many Canadians still don’t realise this is a problem. It isn’t a well kept secret perhaps, but I think that many Canadians would expect such horrific conditions to be considered a national crisis, and because that is not the case, this slips under the radar.

lawlady · November 9, 2012 at 12:17 am

We’re having a rally in Saskatoon November 10th, its a grassroots rally in oppostion of the omnibus Bill C 45. There are two things of concern in there for me; one – the “Aboriginal Affairs” Minister will have more power to extinquish reserve (agricultural) lands. .. two – the protection of water will be compromised and will give oil and nuclear companies easier access to it. I don’t think many people understand the depth of what is going on with Harpers government. I hope that this bill will not pass but it is in its second reading.

Lisa · November 9, 2012 at 4:57 pm

So inlighting, thank you for sharing and providing the resources for us to share far and wide. hai hai

Roger Annis · November 10, 2012 at 11:31 pm

Thank you for this very insightful article. Sadly, it should come as no surprise that “dirty water” and the lack of proper sewage disposal is not only a problem for remote Indigenous communities. Within the limits of Metropolitan Vancouver, the Semiahoo people have been enduring both since 2005, and longer. Yes, within the boundaries of Canada’s second wealthiest city. Meanwhile, the proponent of a casino development on contested Semiahoo land in south Surrey can count on the City of Surrey rushing to provide water and sewage services at the drop of a hat (ok, the drop of a fat cheque). Read about it here:

http://www.theprovince.com/health/South+Surrey+casino+Semiahmoo+joins+protest+against+complex/7521719/story.html#axzz2BqOeWuSd

Don Richardson · November 11, 2012 at 8:05 pm

Thanks for posting this – a very thoughtful analysis. I think there are some systemic design/engineering issues that need to come to light. There seems to be a design/engineering predisposition to complex, high-maintenance, expensive, centralized systems, and some common incentives between those who fund and those who design and build to continue this engineering/design paradigm. Technologies have advanced significantly, but opportunities to reconsider design/engineering approaches can be thwarted by vested interests. There is little or no R&D focused on appropriate technologies and operating water & waste water system design approaches by or with First Nations. The same broken approaches are thrown at the same problems. If you “follow the money” you can understand why this might be so – there are millions involved. It’s time to step back and fully re-assess the entire system – not to fix the technologies, but to fix the system that continues to place often inappropriate technologies at the front of the problem.

Daniel Nikpayuk · November 17, 2012 at 9:36 pm

I wonder what the Inuit version of politics is?

The ways in which people establish and maintain an equilibrium of social order in society is very much based on politics. Social order is a social construct after all, which largely boils down to politics.

I find after years of testing the boundaries of the unknown, of an ever-changing world, that if one wants to establish any influence at all in this modern world (enough to build and have a life), they need to eventually interact in a committed way with institutions; even if one has little or no interest in being upwardly mobile.

For example I myself would eventually like to distribute Inuit culture in the form of art, and as much as I prepare myself with my digital education for this purpose to keep a level of independence, I will still need to negotiate the patterns and flow of distribution with others and thus will likely need to interact with some institution or another at some point or another.

To take things in a slightly different direction, using a more elaborate example, lets say I want to get a Masters or a PhD. I will need to interact with the University on a serious level, and will thus need to be supervised.

In my experience, along with obtaining a formal education in terms of content, people at that professional of a level—often arrogantly—attempt to force their version and understanding of social order on you as “part of your education.”

From my point of view, going into that environment without having an existing worldview of politics is the same as being assimilated. I see it as another form of assimilation. And, if you know me at all, I’m very much against that, instead seeking integration (the key difference is maintaining the right to self-determination).

Education is nearly a universal good, but where’s the incentive if I have to give up my soul in the process?

The extremists in this society a while back figured if they strip us of our social bonds and relationships we’d be “blank slates” and thus much more readily assimilated. As history has shown that doesn’t work. “Trial and error” social theory, using the health and well being of entire peoples whose worldviews aren’t well understood, is not good social policy it turns out.

The thing is, I’ve been stripped of my social bonds, and I figure the extremists figured without all that cultural baggage I’d revert to my true form and be motivated by Adam Smith’s “Greed”. That alone then would motivate me to “get over it”, and thus to pursue a Masters and other such things to help me achieve my personal gain.

Turns out, stripping one’s bonds does not create a blank slate, and what’s more: Creating a blank slate probably isn’t even possible to begin with without some serious ethical oversights. There is wisdom in accepting the differences in others and learning to cooperate and share what would otherwise be conflicting resources. Aboriginal peoples knew (and know) this.

My point is, I’m not overly motivated by personal gain, I’m motivated by people. Where’s the incentive to become assimilated or to at least endure the attempted process (in obtaining a degree or otherwise) if I have no one to support me along the way?

How do I endure another culture’s sense of politics to receive an education or to “grow” my career if I have no barrier / buffer myself?

Fortunately some wise Inuit, knowing the old ways, have had to endure such politics and have come to their own conclusions: “Politics is just another level of hunting.”

This is a problem for me since hunting in the urban south growing up was not a practicality.

Certain “quick-to-judgement” civilised people question what the value of hunting is in the modern world in the first place? Guess what: for a people with a certain worldview it is our means of developing the necessary skills to succeed in life and contribute back to our communities and thus our economies! 🙂

I don’t have those skills but at least I have a hint, something to ponder on and learn about and from.

Maybe I’ll go for my Master’s when I’m 40 or 50, when I have more life experience and a better understanding of the Inuit way of politics in the modern world. Until then i gotta keep doing things my way.

Spencer · November 23, 2012 at 10:01 pm

http://www.younganderson.ca/publications/bulletins/court-of-appeal-confirms-adequacy-of-consultation-regarding-north-cowichan

A decision released today re: water rights. Not a good outcome, but thought you might be interested.

clayton · November 28, 2012 at 7:39 pm

This particular blog was linked by MoccTel and sent to about 1500 native peoples directly. And then sent on to many pools more. I will share a comment (tomorrow because it is at work) regarding my QE medal citing the inclusion of `âpihtawikosisân` as one of distinguishing items that makes my publication unique. Thank you very much!

âpihtawikosisân · November 28, 2012 at 7:56 pm

Many thanks, glad the articles are of use!

Thomas Piwowarski · March 3, 2014 at 7:45 pm

I am an aboriginal who works in water treatment. I want to help communities that have water issues but the government won’t give me a list of communities. It is a very sad state indeed.

Erica · January 9, 2017 at 2:12 pm

that is so gross. why didn’t anyone fix that?

First Nations water problems in Canada : Shenanigans · November 21, 2012 at 10:58 am

[…] This is a disgrace. I am subscribed to this blog and she always opens my eyes. […]

The Sacrificial Alter of Colonialism | kepin omasinahikewin · September 20, 2014 at 9:15 pm

[…] enjoys basic privileges such as the freedom of movement, a properly funded education system, and clean water, indigenous peoples are disproportionately affected by the lack of all three. But this is just the […]

Harvest Thanksgiving | "As I mused, the fire burned" · October 10, 2015 at 8:39 pm

[…] Alexis Sioux First Nation boil water advisory […]

Indigenous Issues: “So what are the solutions!?” | Ecocide Alert · April 19, 2016 at 8:03 am

[…] give you a very specific example. One of the perennial issues in First Nations communities is the lack of safe drinking water. In 2011, Neegan Burnside Ltd. released a comprehensive national report on the state of First […]

People against Water pollution. | Grade 9 Science Journal Q1 · October 25, 2021 at 1:48 pm

[…] Dirty water, dirty secret Singh says there’s no excuse for lack of safe drinking water in First Nations communities NDP’s Singh promises $1.8B to provide clean drinking water in Indigenous communities […]