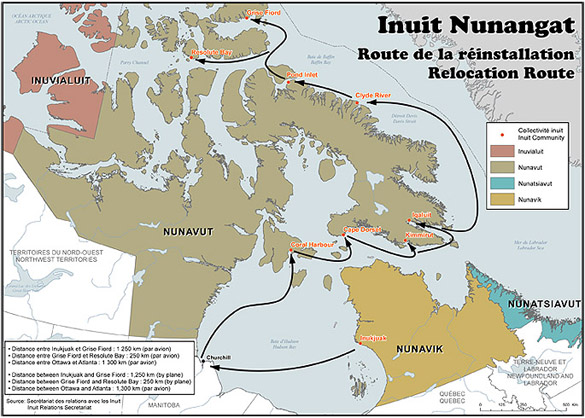

On behalf of the Government of Canada and all Canadians, we would like to offer a full and sincere apology to Inuit for the relocation of families from Inukjuak and Pond Inlet to Grise Fiord and Resolute Bay during the 1950s.

We would like to express our deepest sorrow for the extreme hardship and suffering caused by the relocation. The families were separated from their home communities and extended families by more than a thousand kilometres. They were not provided with adequate shelter and supplies. They were not properly informed of how far away and how different from Inukjuak their new homes would be, and they were not aware that they would be separated into two communities once they arrived in the High Arctic. Moreover, the Government failed to act on its promise to return anyone that did not wish to stay in the High Arctic to their old homes.

– AANDC Minister, John Duncan in an official apology on August 18, 2010.

Relocations of indigenous peoples and even of whole communities within Canada, has been a shockingly frequent event since Contact. In fact, much of the history since Contact has involved relocations of one kind or another. As the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples Report points out, the justification for these frequent relocations was often “this is for their own good”. Yet the RCAP goes on to explain that there are predictable results when relocation is carried out, including:

• severing Aboriginal people’s relationship to the land and environment and weakening cultural bonds;

•a loss of economic self-sufficiency, including in some cases increased dependence on government transfer payments;

• a decline in standards of health; and

• changes in social and political relations in the relocated population.

The results of more than 25 studies around the world indicate without exception that the relocation, without informed consent, of low-income rural populations with strong ties to their land and homes is a traumatic experience. For the majority of those who have been moved, the profound shock of compulsory relocation is much like the bereavement caused by the death of a parent, spouse or child.

Perhaps the blackest eye of all

You may not be familiar with Nunavik. I wasn’t until I moved to Quebec. I kept hearing it as Nunavut for some reason. I am mostly unfamiliar with the eastern Arctic, as I spent my time in the Beaufort Delta and the mixture there was Gwich’in (Dene) and Inuvialuit (Inuit). I am often told that the eastern Arctic differs considerably in many ways. Slowly, I am beginning to discover this for myself.

Nunavik is actually more southern than Inuvik, where I lived for a time. Not all Inuit then are accustomed to 20 minutes of dim sunlight a day during the deepest parts of winter, when the sun merely hovers above the horizon sullenly before sinking back into a long slumber. Nor are all Inuit accustomed to the disorentation caused by 24 hour sunlight in the middle of summer, when you wake up at 3:00 and have no way of knowing if that’s pm or am.

Nunavik is actually more southern than Inuvik, where I lived for a time. Not all Inuit then are accustomed to 20 minutes of dim sunlight a day during the deepest parts of winter, when the sun merely hovers above the horizon sullenly before sinking back into a long slumber. Nor are all Inuit accustomed to the disorentation caused by 24 hour sunlight in the middle of summer, when you wake up at 3:00 and have no way of knowing if that’s pm or am.

It is easy then to imagine the despair one would experience being suddenly dropped into such a different and hostile environment. Even the sanitised, official version of what this was like for the families who were relocated nearly a thousand kilometres north, reads like a horror novel.

At the same time, massive changes were happening throughout the Qikiqtani (Baffin) Region. Understanding the High Arctic relocation in this wider context is very eye-opening. The Qikiqtani Truth Commission held public hearings and gathered testimony and evidence over a period of three years, releasing a final report in October of 2010, and is an excellent place to get that context. (By the way, if you do wish to read that Report, Qallunaat means non-Inuit people.)

This Report is not just a historical tale, or a series of personal accounts, it is also a fascinating glimpse into the concerns and aspirations of Inuit peoples. The Qikiqtani Truth Commission offers numerous recommendations, and makes it clear that there is a desire for saimaqatigiingniq, described as a reconciliation between equals. Another excellent resource is the publication The Inuit Way produced by the Pauktuutit Inuit Women of Canada.

There is much which must be reconciled. What the relocated families endured cannot be undone. I will leave these links here for you to explore rather than explicitly delving into the stories. Those experiences however, took place in a larger context of change, relocation and cultural upheaval.

If you are specifically interested in the High Arctic relocation, you can watch Zacharias Kunuk’s excellent documentary, titled “Exile” here on Isuma TV. It is offered to you freely. Another film, “Martha of the North” by Marquise LePage is available for online viewing through the NFB for only $4.95. (I absolutely love how accessible these kinds of resources are becoming, for serious.)

3 Comments

john lavers · April 30, 2012 at 9:10 am

great references and resourses

Daniel Nikpayuk · May 4, 2012 at 4:03 pm

Hello âpihtawikosisân, it is nice to see topics on Inuit, thank you.

Here is a language consideration for your readers to think over—if could be so bold as to suggest:

“The dog ate the biscuit.”

In the sentence above, if we knew very little about this language, and we saw the substitution: “The cat ate the biscuit.” we might infer a typological system that classifies the words ‘dog’ and ‘cat’ together because they are able to be substituted at the same location within the sentence. If we knew a little more about the language we might say these words are classified as types of “animals.” As an alternative, if we saw the substitution: “The dog ate the cat.” then we may infer ‘biscuit’ and ‘cat’ are a type of “food”.

Just how flexible are paradigmatic typologies: just how flexible is the language to allow substitutions in differing locations of a sentence? “The dog cat the biscuit.” is another such substitution yet in English there are no hermeneutic (interpretive) rules allowing this sentence to have any direct meaning (aside from classifying it as having non-sensical meaning or something similar).

Does the language/culture privilege “typology” or “processology” (I know, I know, I’m looking for a better word…) ? For example one thing I notice about Westerners (sorry to pick on you guys) is that they become uncomfortable with silence; they feel the need to fill it in. I laugh, it’s funny. I’m willing to claim (however problematic) that overall Westerners privilege typology: they use language to create typological divisions and only after do processes like ritual and tradition come into effect. Regarding “silence”, I could be wrong, but it seems to me as if silence is too ambiguous from a typological point of view, there are too many inconsistent and diverse typologies regarding it, which might be one of the many reinforcing reasons why Westerners seem to find it uncomfortable. If one was to consider “silence” from a processological viewpoint, it’s simple: silence is a process, that’s it. It might actually even be a metaprocess allowing the opening up of other processes for substitution (given its strong ambiguity), but that’s another matter. By the way I believe such metaprocesses are translated into a typological view by the word “trope”.

I hope to get through to some of the more “closed-minded” Westerners who have a hard time understanding that other worldviews exist, and that some such views actually privilege “process” over “type”. To take things to extremes to make a point: some languages are more flexible in that they may allow sentences as “The dog cat the biscuit.” to be meaningful. If a ‘dog’, ‘cat’ and ‘biscuit’ are processes, then such a sentence is just a cascading or composition of processes (if one can substitute anything anywhere, the only semantic type would be a “process”), and would allow for direct interpretation. A potential, really crude translation (in which much is lost) could be: “The dog ate the biscuit in the manner of a cat.” assuming we had reason to connect the word ‘cat’ with ‘ate’.

The RCMP killed sled dogs to keep the Inuit in one place. | · December 29, 2012 at 4:29 pm

[…] ensure Canada’s “claim the Arctic” was staked, particularly during the Cold War. They even relocated families into the High Arctic and stranded them there on purpose to fulfill this […]