The following article is my first ‘guest blog post’, by David Schulze, a partner in the law firm of Dionne Schulze in Montréal, which specializes in representing Aboriginal communities and individuals. I think it is important to remember that the immediate problems facing Attawapiskat are still not resolved.

(This article may be linked to or reprinted, but must not be altered. Proper attribution must be made to the author, David Schulze. Images and links were inserted by âpihtawikosisân.)

What About Attawapiskat? Why the situation is not hopeless if we make better choices.

David Schulze, 21 January 2012

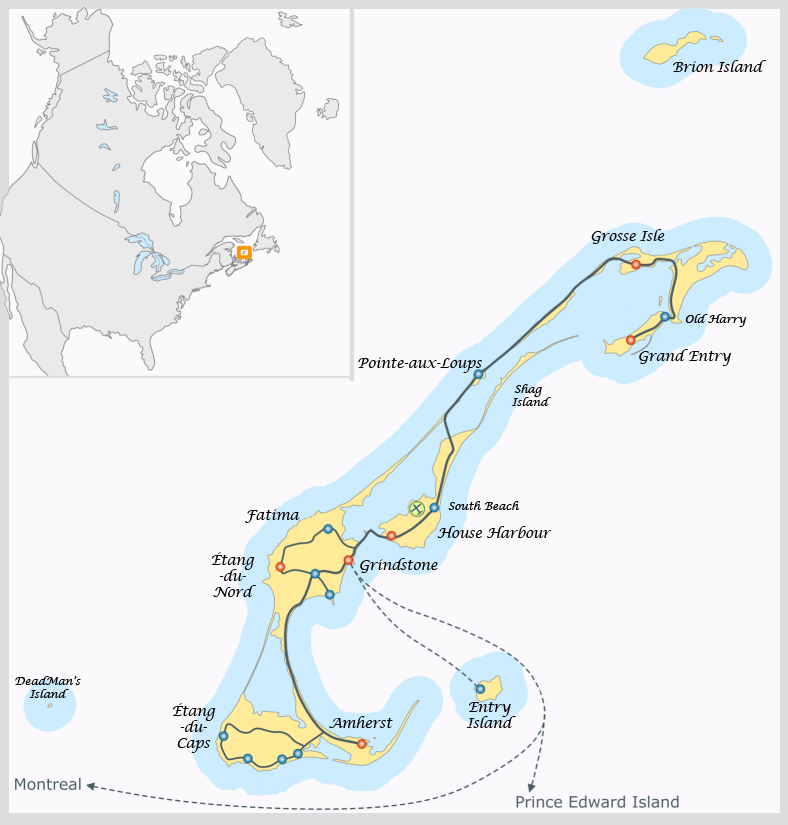

Several yeas ago my daughter and I took the ferry from Prince Edward Island to the Magdalen Islands, a small chain of islands in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence, which are part of the Province of Quebec.

Only 13,000 people inhabit the islands year-round, but tourists flock there in the summer. Most of the islands are connected by land bridges, but sailing in from P.E.I., as the main archipelago comes into view, a ship passenger sees Entry Island, unconnected to the rest of the chain and separated by 12 km of water.

Entry Island has about 130 inhabitants and can only be reached by sea or air. A ferry arrives twice a day from May through December and the island has regular airplane service from January through April.

While in the Magdalen Islands, my daughter and I visited the Anglican priest, whom we knew from Montreal, and he told us that about once a month he went to Entry Island, where all the families are English-speaking, to hold services. Our friend also explained that the provincial government pays for a teacher to live year-round on Entry Island and offer elementary school education to the local children.

As we sailed away from the Magdalen Islands, it occurred to me that in Canada, we see it as reasonable and proper that families like those of Entry Island should have regular transportation services and a public school in their own community, yet similar spending on Aboriginal communities is often viewed as a waste.

As a lawyer, I work almost exclusively for Aboriginal communities. An increasing amount of my time is spent dealing not with land claims or hunting or fishing rights, but funding for programs and services.

Since sailing past Entry Island, I no longer see a reason why my clients should apologize for the amounts their communities cost the taxpayer. Unfortunately, I now think that when Canadians complain these communities cost too much, they are demonstrating an unconscious form of racism.

These thoughts came back to me during the recent controversy about Attawapiskat, a Cree community of 1,900 people situated on the western coast of James Bay in Ontario. It is connected to the outside world only by air, water and an ice road accessible in the winter.

Attawapiskat attracted national attention after declaring a state of emergency on October 28, 2011, due to a severe housing shortage. Many Canadians were shocked when the Red Cross was called in to help.

Several commentators were quick to suggest that the best solution for Attawapiskat would be to shut the community down and move residents to the south, near urban areas.

It seems obvious that this would simply move the poverty elsewhere. The residents of Attawapiskat are predominantly Cree speaking. They live some 1,000 km north of Toronto. The nearest town of any size is Moosonee, which has only 3,500 inhabitants itself, is not connected to the rest of Ontario by road (only by rail and air) and had an unemployment rate three times the provincial average in 2006.

Moreover, Aboriginal leaders have asked why their people should be moved off their land at the precise moment when hundreds of millions of dollars can be made from its resources.

Only 90 km from the reserve, De Beers has opened an open-pit diamond mine employing over 500 workers. Thanks to an impacts and benefits agreement negotiated by the band council, about 100 of those workers are from Attiwapiskat.

Another fundamental question for me is why so many believe we owe so little to the people of Attawapiskat, despite the fact that our federal government entered into a solemn agreement with them in the form of Treaty 9.

Treaty 9 was among the last in a series of “numbered” treaties signed by Canada from the 1870s till the 1930s, with First Nations from northern Ontario to the Rocky Mountains. First Nations surrendered their title to land and in return, the federal government promised them small annual payments, reserves, and the right to hunt and fish throughout their territory.

Representatives of the Crown met with chiefs who usually could not speak English and had them sign legal documents, usually with an “X”. From the government’s point of view, the land had been cleared of competing claims and was ready for settlement. From the Aboriginal point of view, the Crown had promised to protect their way of life.

The Attawapiskat Cree only “adhered” to Treaty 9 in 1930 and in Ontario’s far north, settlers did not follow negotiation of the treaty. As a result, little changed for the Attawapiskat Cree so long as they could still live off the land by hunting, fishing and trapping.

But the 1950s and 1960s saw a terrible combination of circumstances for remote Aboriginal communities like Attawapiskat. The fur trade ceased to offer a viable livelihood at the same time that the federal government pressed the Cree to settle permanently on reserves and enforced attendance for their children in residential schools. The communities were emptied of their children and the parents sat on the reserves waiting for them to return.

Community members had little else to do if they could not hunt, fish or trap. In Canada, infrastructure of all kinds (railroads, highways, schools, hospitals) has always been built for white settlers, for their farms, mines and factories. If Aboriginal communities happened to be nearby (like the Mohawk communities of southern Quebec and Ontario for instance), they benefited from that infrastructure, but if they lived in remote areas like Attawapiskat, they remained isolated.

Even the Indian residential school experience reflected this reality: attendance was most widespread in remote communities were the government did not want to build schools. The federal government took the children out of these communities to more centrally-located residential schools and left them there, sometimes for the school year, sometimes for years at a time.

Since the 1950s, the federal government has progressively provided Indians on reserve with most of the services the provinces provide to other Canadians, such as health care, education, and social assistance. Since the 1970s, service delivery has been progressively delegated to the First Nations themselves.

However, the federal government does not usually take on services to First Nations as binding legal obligations: funding depends on the annual budget and on a Minister’s discretion. Services such as local policing, for example, may simply stop from one year to the next, to be replaced by a distant provincial police detachment.

Moreover, federal funding for services to First Nations does not have to match the level of provincial funding for the same services off reserve. Often, federal funding is lower, even though the First Nations who administer programs are expected to meet provincial standards.

The result in an area such as education is that Indian Affairs provides per capita budgets below the provincial averages to reserves where needs are greater than the in the rest of the province. Communities already faced with the challenge of serving deprived populations in remote locations like Attawpiskat become trapped in a downward spiral of underfunding and underperformance.

During the Attwapiskat controversy, the Prime Minister cited the $90 million in funding provided to the community during the preceding five years and called the results inadequate. But how generous was this funding when Council was providing municipal, educational and health care services, as well as housing, all at a location no car or truck can reach in summer and where the cost of building a single home is $250,000?

Nor are First Nations unaccountable. The Auditor General has reported that their councils file literally hundreds of financial reports every year to various federal government departments. The Minister of Indian Affairs reacted to Attiwapiskat’s crisis by placing the council under “third party management”, a form of trusteeship the Minister reserves the right to impose when a First Nation’s deficit reaches a set proportion.

The most important point, however, is that things do not have to be this way. Clear evidence contradicts the commentators who insist that the problems of remote First Nations can never be solved, that no amount of money will make things better, that we must shut down communities like Attawapiskat and encourage their residents to leave their traditional lands.

Just across James Bay, on the east coast, the example of the Cree and the Inuit living in Québec proves that life could be much better for communities like Attawapiskat. Life in the Cree and Inuit villages of Québec is far from perfect, but it is significantly better than in the Cree communities of northern Ontario.

Unlike the James Bay Cree of Ontario, no-one asked the James Bay Cree and Inuit of Québec to sign a treaty as a pre-condition to development. On the contrary, the Québec government announced in the early 1970s that the James Bay hydro-electric project would flood their traditional lands without even informing them of its plans.

The Québec Cree and Inuit went to court to stop the James Bay hydro project and obtained an injunction, though it was quickly set aside on appeal. Settlement negotiations with the federal and provincial governments led to the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement (JBNQA), the first modern land claims agreement, signed in 1975, after which the project went ahead.

Among other things, the JBNQA left the Cree and the Inuit with regional school boards, health and social services agencies, police forces and local government structures under their control. These institutions are funded jointly by the federal and provincial governments, to the same level as comparable bodies in the rest of the province.

The JBNQA also recognized their right to hunt, fish and trap and provided the Cree and the Inuit with a role in wildlife management and environmental assessment on their territory.

With the compensation paid to them for settling their land claims, the Cree and Inuit bought the airlines that serve their communities, among other businesses. Where Attawapiskat derives benefits from a single mine, the crucial role played by the Québec Cree and Inuit in deciding on the development of their territory has led to a growing role in many areas of the regional economy. In businesses such as mining, forestry or commercial fisheries, the Cree or the Inuit participate through royalties, employment, or ownership.

The question raised by the example of the Cree and Inuit of Québec is why they had to go to court and accept massive development on their lands in order to obtain the benefit of adequate locally-controlled services and economic opportunities of the kind we would consider a minimum for other Canadians?

The real question raised by Attawapiskat is whether all we promised its people in Treaty 9 were underfunded resources on unsustainable reserves and an invitation to move elsewhere if it does not suit them? Or is it possible that we owe them institutions and services of at least the same quality we take for granted in the rest of Canada and a chance to participate in the economic benefits that can be derived from their lands?

22 Comments

Dave Jones · January 23, 2012 at 10:20 am

I am of the view that “we owe them institutions and services of at least the same quality we take for granted in the rest of Canada and a chance to participate in the economic benefits that can be derived from their lands.” I have been poo-pooed in the past for suggesting this, but I think that a positive (first) step for the federal government would be to construct a rail line through the north that would link these communities to each other as well as supply centers. This would help lower costs of housing, food and supplies and give year round access to amenities in the south.

It also appears that there is a leson to be learned from the Cree and Inuit of northern Quebec.

Yvette · January 23, 2012 at 11:48 am

What we need is transparency of contracts, with the government, mining companies and so on. This will increase accountability. No need for secrets. Attawapaskat has thrown open its closets. Let us see inside the government and the mining companies closets too! Put the contracts up on the web.

The other thing is evident to me the use of language regarding the on going First Nations-Settler relationship needs to change from pity words for First Nations positions to words that represent a legitimate negotiating partner. For example the choice of the word ‘promise’ as in the government promised …. This is a terrible and even destructive word choice, as it implies a generosity to a weaker party. Positions of strength and weakness or power and victims should be sanitized from conversations about this topic. Otherwise there is an implicit acceptance that the feds representing authority (although they have run a pretty tight game-they aren’t!!), and/or relinquishment of First Nations’ power (which they have fought hard not to give up!!). Don’t get me wrong, I understand that these contacts are complicated and steeped in cultural miscommunication, manipulation and power grabs. What I am saying is that these conversations could benefit from the use of language that acknowledges the legally just position of First Nations in these negotiations.

Dennis Goos · January 23, 2012 at 2:06 pm

I really enjoyed reading comments that express the viewpoint that so many Canadians hold. As a renter, I live on an urban reserve, a quite well-off reserve compared to more isolated places. But even here, the differences with abutting municipalities are glaring. Roads and sidewalks, housing standards, and poverty disappear as soon as I drive off the reserve. There is no justice in this.

My friends off-reserve are blind to the abusive treatment because they accept the racist judgments that are placed on First Nations peoples and so confidently expressed by the non native majority in Canada.

The local band holds a celebration each year in early summer and invites all their neighbours to share in a free feast as their way of promoting understanding. Only officials from the non-reserve community attend. Racism blocks the rest.

It saddens me. I don’t know the solution but it is not in the hands of First Nations people. To paraphrase a joke: Racism is not the answer. Racism is the question. “No”, is the answer.

Cynthia Preston · January 24, 2012 at 12:08 am

“I don’t know the solution but it is not in the hands of First Nations people.” Dennis Goos

It is and it isn’t. Persistence is, in the hands of First Nations people, as wellas those of us who have always had a curiosity and a desire to understand, to listen, to affirm, to hold accountable the government, to speak out against misinformation. We can make all the difference in creating change,

I have noticed in the days since Attawapiskat first hit the headlines, the number of Documentaries, TV presentations, etc concerning Canadian First Nations, and non treaty Indians, has begun to take on the presence of a slow but steadily growing snow ball like those created by the wind after a fresh snow along Prairie highways, just waiting to be pushed to the tipping point of a down ward slop long enough to create really really big and noticeable snow ball!

As each of us try to do our part, to spread the links to knowledge, to breakdown prejudice. We were the silent, but frustrated, who now have the means to aid in overcoming injustice, in a way we never had before. Because its the RIGHT thing to do.

Mr. Harper may find his ticket to success in the next election is how well he addresses, the inadequacies of the federal governments servicing of its treaties and of those who have no treaties.

Dennis Goos · January 23, 2012 at 2:08 pm

Should have edited that post. Read it with understanding that interprets the glaring errors, please.

âpihtawikosisân · January 23, 2012 at 3:35 pm

Looks good to me!

scansite2 · January 23, 2012 at 3:17 pm

This is a great explication of the quandary we all — can-originals and cans-from-away — have made for ourselves. The answers to the two questions in the final paragraph are, “No” and “Yes”. The answer to the question in the penultimate paragraph is that no-one has any idea what would have happened in Nunavik — where my daughter and granddaughter live — if it hadn’t been for the James Bay hydro development. It’s quite possible there would be more Attawapiskats there.

I take some exception to the following: “. . . we see it as reasonable and proper that families like those of Entry Island should have regular transportation services and a public school in their own community, yet similar spending on Aboriginal communities is often viewed as a waste.” Nobody thinks spending on education and decent transportation for First Nations is a waste. What people think is that money that is provided for these services is often wasted by mismanagement. It’s only possible to get to the bottom of the question by digging into details that aren’t readily available.

If $90 million over five years too little for 1,900 people living in northern Ontario? It amounts to under $10K/person/year. This isn’t all the revenue in the community? Is it fair? Is it enough? I don’t know. What I do know is that when things reach the stage they have at Attawapiskat somebody has screwed up big time and there’s enough blame to stretch all the way from Ottawa to James Bay.

âpihtawikosisân · January 23, 2012 at 3:34 pm

If comparable funding to First Nations is not seen as a waste, then what? What is the rationale behind chronic underfunding? I agree that it might be too easy to characterise the situation as being about perceptions of ‘waste’, but there is clearly something at work that makes it digestible to underfund First Nations and not other isolated non-native communities in areas like education and health care.

scansite2 · January 23, 2012 at 5:17 pm

It is not “digestible to underfund First Nations and not other isolated non-native communities in areas like education and health care.” At least it’s not to me. But again, this discussion requires a lot of detail and understanding of living conditions, sometimes quite voluntarily accepted, in various communities. Things have been pretty tough in Newfoundland outports, for instance. (Of course, there are no Beothuk there any more because they were wiped out by the Euros, which isn’t much of a solution.) One of the biggest problems of understanding is that the discussions are too often about ‘all of us’ and ‘all of them’ while no such communities of the whole exist. There are bigots and idiots on both sides, probably in equal proportion. But it seems to me that Aboriginality has made significant progress in my lifetime. Why the good guys don’t seem to be able to get a better handle on things is something of a mystery.

âpihtawikosisân · January 23, 2012 at 7:35 pm

It might not be digestible to you personally, but it is certainly digestible to the wider Canadian public. I am sorry, but I do not accept that the wider public is sympathetic to First Nations, or finds the funding disparity unconscionable…because I have certainly seen little evidence of such, individual claims to the contrary.

There is a very clear level of support for the status quo which includes underfunding to First Nations, bolstered by a sense that any funding takes advantage of ‘real tax payers’. When not expressed in such obviously bigoted ways, the claims of ‘mismanagement’ (so perfectly highlighted by the truly ugly dialogue around Attawapiskat) provide a more socially acceptable way to justify everything from underfunding to advocating that people be moved out of their communities. These accusations of mismanagement do not even require evidence. The belief that First Nations are corrupt and mismanaged and are unaccountable are seen as being ‘common sense’.

There are a few ‘soft words’ in your comments that ring bells, to be honest. “Conditions…sometimes quite voluntarily accepted”. “No such communities of the whole exist”, “bigots and idiots on both sides, probably in equal proportion”. Yes, it is good to recognise that there are no absolutes, no totally good, no totally bad…but when people attempt to portray things in a way that suggests really, things are the same wherever you go, it minimises the quite serious instances of inequality. Things are not equal. Situations in native and non-native communities are not particularly comparable. There can be some common ground, yes, but this does not level the playing field. There is not an equality of power which means that so-called ‘bigots’ in native communities can somehow be compared to bigots in non-native society who do have power and who are backed up by systemic racism.

I’m sorry to be focusing this on you, because I’m sure you mean well. Nonetheless, I have to caution against ignoring the reality aboriginal people struggle with. A reality in which we certainly are not treated the same or afforded the same opportunities. A reality in which wide public perception is extremely negative, and often hostile. I think that has a lot to do with why ‘the good guys’ haven’t won.

scansite2 · January 23, 2012 at 10:10 pm

I think you play a lot with words. Some that I think are just informative you seem to find incendiary. You object to certain phrases, intimating that they arise from some misunderstanding of the great harm that has been done to First Nations’ people and the great misery that many of them live in. At the same time you’re comfortable with blanket assertions, such as ” . . . I do not accept that the wider public is sympathetic to First Nations, or finds the funding disparity unconscionable . . .” I can point you to a number of public opinion polls that indicate quite a lot of sympathy. But of course finding the funding disparity unconscionable actually requires knowing quite a bit more than appears in your average Postmedia outlet. And to twist the point that there are some (Newfie outports) parts of non-native Canada that are pretty hard done by, into an “attempt to portray things in a way that suggests really, things are the same wherever you go,” would only be fair in a verbal scrap where it could be immediately countered.

âpihtawikosisân · January 24, 2012 at 9:06 am

I do not want to attempt to have a debate via the comment section, but I would like to explain further why exactly I object to some of the things you’ve said. I’m not going to go into every single one, just the first instance. You are free to disagree that my interpretation flows from what you actually intended, and I will accept this.

In your first comment you made it clear that you think funding to First Nations ought to be of the same quality as those given to Canadian communities and institutions. We certainly agree.

You go on to object to the following from the article:

Your objection was phrased as follows:

I disagree that there is a significant difference between the two. Both views are prejudicial, and hostile towards First Nations. Both are predicated on the concept of ‘waste’, justified in any variety of negative ways (from ‘they don’t deserve any money thus it’s a waste’ to ‘they are too inept or corrupt to handle money, thus it’s a waste’).

In my view, challenging the statement made in the article by offering an equally negative alternative, is confusing. It suggests a number of different things, with little clue as to what was actually meant. Is the alternative being offered as not-that-bad? Is it okay that the general public is ignorant of the details and thus cannot verify if their negative beliefs are justified are not? Does it matter how Canadians think money is being wasted, if that is the general opinion (which you seemed to agree was the case)? Perhaps the nuance does matter if we want to address it, but the way it was presented “no one thinks it’s a waste! They just think it’s wasted” struck me as quite odd.

I have provided links to many sources in the Learning Resources section of this blog to back up my references to widespread Canadian sentiment towards First Nations. I deliberately chose sources set up within the Canadian system so that there could be no claim of inherent bias against Canadian socio-political institutions. I would be interested in seeing the opinion polls you have mentioned.

Rhoda · January 23, 2012 at 10:27 pm

Bravo!

Jim Poushinsky · January 23, 2012 at 11:54 pm

The Province of Ontario has long been building “Roads to Resources” through the northern Ontario wilderness for the economic development of natural resources. When the taxpayers of Ontario are paying for roads and infrastructure for private corporations to reap profits for the 1%, there is no excuse for not building similar all-weather roads to reach Ontario’s human resources on First Nation reserves. Likewise there is an urgent need to provide affordable high speed internet to all remote or rural areas. Providing decent road access and modern communications to all communities in Ontario should be a no-brainer! Why isn’t this a priority at all levels of government?

Wynn Currie · January 24, 2012 at 2:11 pm

I think that the whole story is not given here about Entry Island, Magdalen Islands.

First as the population decreases, the services are decreasing and for the size of the population, they bring in an larger per capita income to the economy of the islands as a whole. The work force spend many long hours in fishing boats, 6 days a week, 9 months a year, often on rough seas, bringing in large catches of many types of fish as they come into season.

Soon the school on Entry will be gone. There will be no government money to continue this. The road system has never been paved and often has eroded. The Anglican ministers are now gone from the islands completely. Other than the ferry service, the plane during the winter when the ferry closes, Hydro electric power (all of which they pay to use), an out patient clinic (nurse is a long-time resident of the island, who is restricted no more than flu and vaccination shots) and presently minimum education services, the people pay out of pocket for what they have.

The people of Entry Island receive less benefits than people of the Maritimes, because of the size of their population which is why the population has decreased by two thirds in the last 30 years. They are leaving the island so that they can have access to such services as paved roads and have good public education for their children.

I don’t wish to take away sentiments from native difficulties but don’t exaggerate the handouts of the government to the people of Entry Island as a comparison. I’m not an Entry Islander but I see those people working really hard for what they get and they always did.

âpihtawikosisân · January 24, 2012 at 7:49 pm

Nonetheless, there are not long screeds in various national newspapers demanding that these people be relocated.

The drain from rural or isolated communities towards urban centres because of lack of local economic opportunity can be felt across Canada, and is one of those issues that can be seen as being in common with isolated native communities…but the differences are still important. It seems to me that the author is trying to make the point about the difference in perception towards isolated and arguably non-economically viable communities based on whether those communities are native or not.

scansite2 · January 24, 2012 at 8:23 pm

I disagree. I think the point the writer is making is: “I don’t wish to take away sentiments from native difficulties but don’t exaggerate the handouts of the government to the people of Entry Island as a comparison.” It’s simple. Declarative. And it doesn’t minimize the differences. It just doesn’t make them all important.

âpihtawikosisân · January 24, 2012 at 8:35 pm

I was referring to David Schulze, the author of the article to which the comment in question was directed.

Emo · January 24, 2012 at 3:24 pm

Photographs of a mother and child on the Attawapiskat River in 1941.

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-HDuX-4JO8ZE/TwIBqiektaI/AAAAAAAAAQA/oTIvVmBi29o/s1600/NMP7001.jpg

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-dg5iKSRML0s/TwIDccls8QI/AAAAAAAAAQY/ba45OU0R4Rs/s1600/NMP6932.jpg

How’s that for a different perspective on the issue?

âpihtawikosisân · January 24, 2012 at 7:23 pm

Beautiful pictures. Thank you.

e.a.f. · January 24, 2012 at 5:12 pm

Nothing much has changed for First Nations People because the politicians and a majority of Canadians don’t care. Politicians care when it comes to votes to be collected and small settlements don’t cut it for them.

First Nations People didn’t have the right to vote in this country until I think 1960. I have never understood that. Citizens of this country denied the right to vote. If other communities have the right to clean running tap water in their homes then why is it denied to First Nations People? When people died in Waterton because of unclean water there were investigations, criminal charges, the whole country sat up and watched. On reserves, dirty water is Canada’s dirty secret. It is very sad indeed that Canada will spend money in foreign countries to provide clean water but not in their own country.

Education is essential for all reserves and in my opinion it must be provided on each reserve. For families to succeed and children to grow up strong they need their parents and grandparents on a full time basis. To send children to “boarding” schools and away from their homes is a violation of their rights.

I do not know what the solution is but it seems embarassing the government seems to have worked this time.

Mar. 16: Ed Bianchi and Indigenous rights in Canada; local musician Rayven Howard in studio « OPIRG Windsor's The Shakeup: Radioadvocacy Friday 4 -5PM EST · March 19, 2012 at 7:42 pm

[…] injustice and marginalization than Aboriginal peoples in Canada. Recently, news from Attawapiskat (Blog post) on the west shore of James Bay was a big media event for the exposure of the poverty there, and […]

Comments are closed.