“Years ago while visiting his grandma Lucinda Robbins in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, CEO Don Thornton purchased a Cherokee-English Dictionary written by a professor from the local University.

When he showed the dictionary to his grandma, she commented in a frail but angry voice: “That man used to come to my house for three years asking how to say words in Cherokee. Pretty soon it would be lists of phrases. I fixed his lists for three years and all I wanted was a copy of the finished work but never received one.”

Don flipped through the pages of the entire dictionary looking for her name but Lucinda Robbin’s name was nowhere to be found. She was not credited for her work, not only that, she was never paid and did not even receive a copy of the work.”

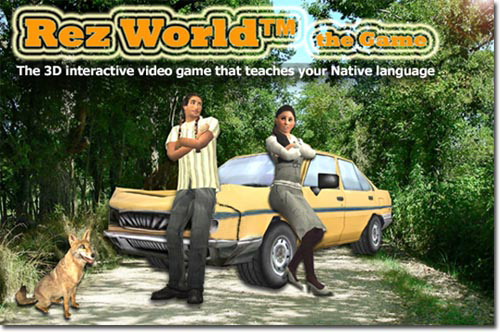

This anecdote used to be shared on a now-defunct website for a Sims-like game called RezWorld. Someone tweeted a link to the site many months ago and I was nearly incoherent with excitement. I immediately watched the video describing the project and started scanning the site to see where I could buy it.

That’s when I noticed that the demo had been released in 2008, but the project has not gone any further since then due to a lack of funding. I was disappointed but not surprised.

There are three very important issues raised by this one stalled language development project.

- One is the way in which our fluent speakers and communities feel they have been taken advantage of, and what this has done to the state of language development in Indian Country.

- Two is the lack of a real commitment to the preservation, revitalisation and development of indigenous languages by any level of government.

- Three is the way in which we continue to spin our wheels, developing the same kinds of language materials over and over before burning out or running out of funding and quitting.

I want to point out that I am building on an earlier post that will provide ‘missing context’ if you finish this post and wonder why I ‘left some things out’.

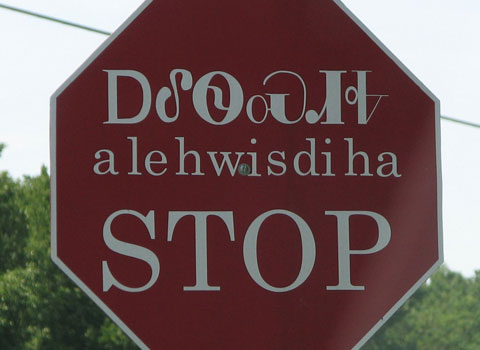

Suspicion in our communities

Whether completely founded, mostly founded, or some other combination of founded and unfounded, there exists a strong amount of suspicion in our communities when it comes to people being interested in our languages.

A widely held belief is that outsiders commonly engage in the kind of thing described in the opening quote. Meaning they take from the community the time and expertise of our fluent speakers, without giving back.

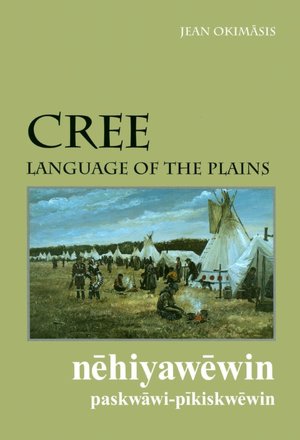

Over the years I have heard many complaints about language materials being developed by universities, with the copyright ending up in the hands of the university in question, causing these materials to be less than accessible to the people from that particular language community.

For example, if you want a copy of the Cree language workbooks I have, you need to either physically go to the University of Alberta bookstore, or get a friend to buy them for you. They are not widely available, and you will not have access to the oral materials that go with the course.

I would of course suggest to you that if you have an interest in Cree, you hit up the incomparable Dorothy Thunder at the Faculty of Native Studies, and take some classes. However as I am keenly aware, not everyone can make it out to Alberta, nor afford the tuition.

Collaboration or alienation?

Our languages are rich and diverse and beautiful. They have also been taken from us through decades of systemic cultural abuse. One can certainly understand then how difficult it is to believe that anyone from the Canadian system can ‘help’ us regain those languages.

We transmitted our languages to each new generation without the aid of writing (in most cases), without the aid of digital recordings, and without the help of non-natives. Massive interference in this cultural and linguistic transmission has led to a less than stellar relationship between natives and non-natives, and regardless of good intentions, the insistence that our languages be regained via western systems of learning, rankles.

Unfortunately, we no longer have the support system in place to transmit our languages in the traditional way. Even in communities where fluency has remained fairly high, encroachment of English or French is becoming a serious concern.

Perhaps even more disturbing, is the fact that the majority of people studying indigenous languages full time, are non-indigenous. There are numerous socio-economic reasons for this, but increasingly the ‘keepers’ of our languages are settler academics. I suspect that just putting this out there is going to offend some people, because of course, I have implied that this is a bad thing. This leads itself to the leap that I am saying settler academics who study our languages, are bad people.

I am not in fact making that claim. Some settler academics become so involved in our languages and cultures and histories, that they essentially become part of those communities. They may marry in, or simply begin living their lives in a way that makes them part of our kinship groups. These things are possible whether or not someone is studying our languages. Others choose not to integrate themselves in that manner, but are still not intending to do any harm to us or our languages. Whatever the motives, what worries me most is that ‘language expertise’ is increasingly being taken outside of our communities and into institutions that are beholden to concerns which are not centered around indigenous world-views or aspirations.

The focus of these academic pursuits is to study our languages and understand how our languages work. For us as indigenous peoples, the structure of language is much less important than the use of it. For those that would argue we cannot do one without the other, remember that we learn languages as children without being told what conjugation is, or what pronouns do and how to use them. (Yes, I am aware that linguists understand this.)

What cannot be understated is the way in which the history of colonisation within systems of education in Canada have impacted indigenous peoples, even those of us who did not directly experience the Residential Schools. I would love to discuss this in much greater detail, but suffice it to say that for many of us, academic institutions are incredibly alienating spaces and if it continues to be the case that these are the only spaces we can access our languages, then we will continue to see very few indigenous peoples willing or able to do so.

Lack of commitment

Despite the fact that in Nunavut and the Northwest Territories, laws have recently been passed giving official status to indigenous languages within those territories, we are losing our languages at frightening speed. There is no comprehensive attempt to deal with this either at the federal or provincial level. Some provinces have developed curricular documents and have funded the creation of resources and even language programs, but nowhere outside of Nunavut are indigenous languages given equal standing with French and English.

Francophones are keenly aware of what less than full commitment means to the retention and transmission of their language, and francophone communities outside of Quebec have been very vocal on the subject. They have had to fight very hard to ensure accommodation under the Constitution, and some communities have been successful in creating francophone boards of education and so on. Nonetheless, even these communities struggle with language loss. Now consider the lack of Constitutional protection for indigenous languages, and the subsequent lack of political power to create and receive funding for indigenous school boards. We cannot half-ass it. What is being done now to support our languages is simply not enough.

Francophones are keenly aware of what less than full commitment means to the retention and transmission of their language, and francophone communities outside of Quebec have been very vocal on the subject. They have had to fight very hard to ensure accommodation under the Constitution, and some communities have been successful in creating francophone boards of education and so on. Nonetheless, even these communities struggle with language loss. Now consider the lack of Constitutional protection for indigenous languages, and the subsequent lack of political power to create and receive funding for indigenous school boards. We cannot half-ass it. What is being done now to support our languages is simply not enough.

Reinventing the wheel time and time again

I have spent a ridiculous amount of time and money over the years gathering together as many Cree language resources as I can possibly find. I have dozens upon dozens of books and websites and curricular documents and so on. The latest thing are the apps.

Curricular documents give us the opportunity to teach the language within a framework, but you still need an instructor. Grammar resources and dictionaries are essential for language learners, but they also require an instructor to be of any real use.

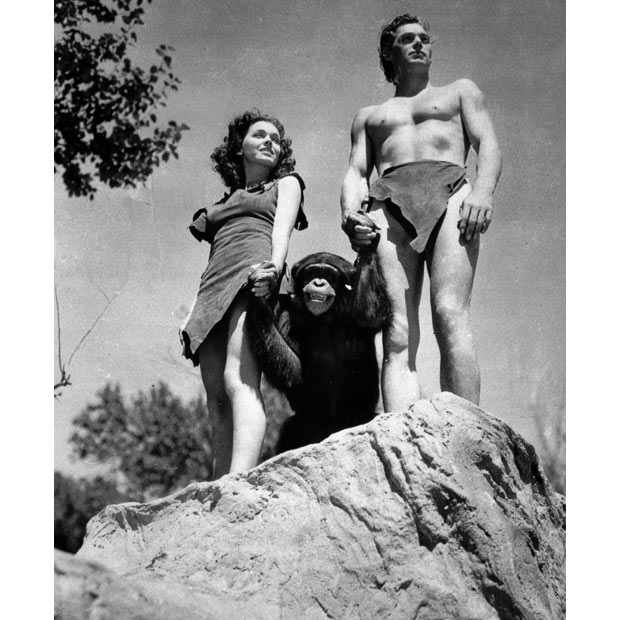

Most of the resources available are repetitions of the same themes. Colours. Animal names. Parts of the body. Kinship vocabulary. Almost of all of these resources were created by individuals and organisations who were passionate about the Cree language. Yet by and large, these resources ares stuck at the “Tarzan at the party” stage.

There is a method of evaluating language fluency that Khelsilem Rivers (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh-Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw) introduced me to called “Travels With Charlie” which involves four levels of proficiency:

- Level 1: Tarzan at the party. “Beer!” “Good party.”

- Level 2: Going to the party. “Where is the party?” “How do I get to the party?”

- Level 3: Discussing the party. “What happened at the party last night?”

- Level 4: Charlie Rose. “Should parties be illegal?”

Each level of proficiency requires more complex levels of fluency. I am only at a level 3, and sometimes able to pop briefly into level 4. That has become less and less true as I lose my language from lack of use.

The materials I have collected over the years fit squarely within level 1. As a result of the lack of commitment I briefly discussed earlier, most of these projects were started by passionate individuals or community organisations on a mostly volunteer basis. Some organisations have been successful in acquiring temporary funding, but there is no central ‘Cree Resource Development’ group with serious funds and expertise available.

Instead, people like myself recognise a serious need for resources for classrooms or for use in the home, and we make them. We might even try to get funding, but eventually we burn out and the money dries up. What is left is only the beginning of what is always a larger development plan. As a result, if you want to learn animate and inanimate colours in Cree, you’ve got dozens of resources to choose from. If you want to learn how to talk about the party last night, you’re out of luck unless you can afford to study the language formally somewhere.

It is absolutely vital that we do more than recognise this reoccurring problem. And I really do mean reoccuring. I have resources from the 70s that essentially mirror apps that are being put out right now. Groups like the Cree Literacy Network acknowledge that common effort is needed, and attempt to promote this collaboration, but something is still lacking.

This is not just about money, this is also about coordination and sharing of expertise. We have so many people out there on their own, trying to do the same things over and over again, not even aware of one another. We have Language Nest programs in some communities that are doing very well; we have unique community-based schools that successfully integrate cultural learnings and graduate academically competent students. We have people creating online and print resources, apps and so on. We even have people offering free language classes in urban centres. It often feels to me that we are going in a thousand different directions, and in doing so we are all beating the same path without really moving forward.

I do not have answers for this problem because I feel mired in it. I am frustrated by the fact that many of us are too busy putting food on the table to even have the opportunity to study our languages much less develop resources in them. I am frustrated by the lack of funding and commitment on a wide level. I am alienated by the relocation of language expertise into expensive and often inaccessible institutions of learning. I am inspired by the many people who devote the time and energy they do have to finding ways around these obstacles, and I hope that we can find a way to pool our resources, and share our successes.

This is less an article than an invitation for discussion, so please…what roadblocks do you see, and what suggestions do you have for overcoming them?

18 Comments

Trish Hurley · October 3, 2013 at 11:38 am

This is one of the best articles I have ever read. I don’t have answers, but I agree with you entirely.

Perry Bulwer · October 3, 2013 at 11:55 am

A very important issue. Perhaps one small but important solution, or at least a beginning, is the movement to restore many original Indigenous place names for important geological features, such as Mount Douglas on Vancouver Island. see:

http://www.timescolonist.com/news/local/it-s-pkols-not-mount-douglas-marchers-proclaim-1.228920

Since shaming was used on many Indigenous children to force them not speak their language, restoring pride in the use of Indigenous languages could help push interest in learning or relearning those languages.

Bruce Weaver · October 3, 2013 at 1:45 pm

Thank you for such a great article. Helps explain the difficulty that I am having to find any Mohawk resources, other than at the University level.

nellymills · October 3, 2013 at 2:58 pm

skype conversations – 30 minutes – level 4 speakers may be willing to give 30 minutes a week to original language conversations to boost others abilities. network is the key. thanks for this passionate plea.

daveM · October 3, 2013 at 4:18 pm

Can you create a central repository type vehicle on the cloud where people can post queries and ideas and replies so that things are accessible to all interested parties. There may be a corporation that will donate the space as it would be a large project.

Daniel Nikpayuk · October 5, 2013 at 3:57 am

GitHub.

No need to reinvent the wheel.

daveM · October 5, 2013 at 10:52 am

Would you be able to outline some sort of info gathering setup that would satisfy the requirements as outlined so far….. so that interested people could get some idea as to how it would work….

My thinking is that a central repository would be a great start and that as time passes people could actually seek specific items, especially if there was a format to follow…. This would be huge undertaking.. A comprehensive format would go a long way to get the project off the ground.

Thanks for your suggestion, I think your idea can be turned into a most useful resource.!

Daniel Nikpayuk · October 6, 2013 at 3:03 am

I have a personal GitHub account already, but I am now in the process of setting up a new GitHub account for the purpose of building a collective and collaborative, open and central, repository. I will get back to you on that matter.

In the meantime, I recommend this article that eases “non-techy” people into using GitHub and why using it is a good thing:

http://readwrite.com/2013/09/30/understanding-github-a-journey-for-beginners-part-1#awesm=~ojtiYP0xnmihuh

Thanks.

daveM · October 6, 2013 at 5:40 pm

Wow……….. this is tremendous. a start.!

Many people will thank you for your contribution…..!

Daniel Nikpayuk · October 7, 2013 at 4:46 pm

Okay, here it is:

https://github.com/Cree-Literacy-Project

Please click on the “Click-Here-For-Beginners” link and read the “README.md” to get an idea of the intentions.

GitHub has a small learning curve and I don’t want that to scare anyone off. I’ve chosen it—and am promoting it—as it really is a small learning curve, and it is the technology best suited for online consensus based governance and decision making for projects and conversations such as this.

I have volunteered to be an administrator, but will take no offence if the approach does not take off or if someone else is decided to be better suited.

In such a case I will not be offended, such is the risk of participation—the participation inspired here by Chelsea Vowel and her blog.

Thank you.

Sandhu Bhamra · October 3, 2013 at 4:49 pm

What a deeply-moving, insightful piece. I don’t have answers and I know you are not looking for answers, as: uh, I understand! uh, how brutal! And I am not writing to say such a thing. It makes me think what a layered challenge it is.

But I must point out to your comment, “For us as indigenous peoples, the structure of language is much less important than the use of it.”

Brilliant.

As a woman of colour and immigrant, I can relate so much to this. Post-colonialism, when academics outside of the culture study our culture and language as how and what makes it “work”, it confounds me: are you helping? If yes, how?

Following the history of colonization of India (where I come from) – Sanskrit language has faced the same fate. No common person in India can speak it (or understand it for that matter), except for a few mantras that are only understood with their translated meaning. It has been academically studied, dissected, and debated by the people outside of the culture with the result that the holy, sacred verses have been given a whole new meaning! Now if modern day Indians study it, they spend a considerable time just defending the language and its meanings, instead of adding new scholarship.

Bruce · October 3, 2013 at 10:55 pm

Check out creewarrior on youtube, the Cree program is the work of the students in the Cree programs at Blue Quills First Nations College just east of Saddle Lake AB. some nice clips and awesome work preserving, promoting the Cree language.

john · October 4, 2013 at 9:55 am

great article. language is essential to culture. I spoke gaelic(gaidhlig) until five years old. our language is now an academic study in Canada. the loss of the language also has hearalded the loss of the traditional culture in any authentic form. it is the same for all languages.

nmr · October 8, 2013 at 9:40 am

I don’t know if this is going to be very helpful to you, but I thought I would throw out some ideas and perhaps you will be able to think of something better.

1. target audience: I know, in general, parents tend to try and teach very small children language. But often, young people (late junior high- early college) get interested in their roots and are self-motivated to learn their ancestral language. Are there ways to market language programs to this youthful audience? A lame example, with a little nudging I got the theme for our public school multi-cultural fair to be “language”. All the booths from the different countries need to have something on their display about the language of their people (alphabet, “how do you say..”. famous poets, how language is conveyed- scrolls, oral, books, etc). Sometimes a public venue like this is enough to stimulate someone’s curiosity. I saw a movie where the Miss Navaho Beauty Pageant (yes, I know beauty pageant- but this is the most common way to give girls scholarships) has a required language portion.

2. I think you need to add an extra Level 5: (not sure what to call it here) Robert Frost? The ability to write poetry in the language, to convey meaning and emotional resonance through the medium of words. I know that most of the time poetry is considered the apex of language skill, but perhaps you could invent new forms (ex. haiku) which are simple and yet allow even the Tarzans at the party to express themselves and demonstrate how their culture adds greater spiritual depth to their lives. Hip-hop Cree?

Cynthia Nugent · October 8, 2013 at 12:11 pm

I am really learning a lot from your excellent posts. Thank you for these. Regarding children’s books, I wanted to pass on news about the work of Metis author/illustrator Julie Flett. Her new books published by Simply Red and Orca will both have separate editions in Cree and several other First Nations languages – not bilingual texts, but separate editions. Is this a Canadian first? She is very highly regarded by the publishing and academic community in BC. Her Michif alphabet Owls See Clearly At Night won the BC Book Prize. She will be featured at the Vancouver Children’s Literature Roundtable illustrator breakfast this month. http://cwillbc.wordpress.com/2013/09/29/seriously-exquisite-illustration/

The Roundtable practically never has a local artist at the annual breakfast, which I think is a mark of how highly regarded Julie Flett is. Her boardbook with Richard Van Camp, Little You, is amazing. The head of UBC’s Master of Children’s Literature program wrote the definitive history of picturebook publishing in Canada called Picturing This. She gives a lot of space to the injustices done to First Nations people by Canadian publishing, so I am pleased to see some changes finally taking place for children’s book creators like Julie Flett, Michael Kusugak, and Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas.

Again, thanks for you wonderful articles.

Cynthia Nugent

Nikki · October 28, 2015 at 10:31 pm

I was wondering whether you find it offensive for people like me—I immigrated to Canada from Eastern Europe when I was a child and obviously have no Aboriginal background or ties to present-day communities—to learn some Cree simply because I find it interesting and relevant to where I live. It seems that you are suggesting that it is upsetting that outsiders will often have more opportunities to learn the language than those who are actually from the culture. Is there a way to learn a bit about the culture and the language (I wouldn’t be able to make a longterm commitment to becoming a fluent speaker or making longterm ties with communities) without exploiting it?

âpihtawikosisân · October 30, 2015 at 6:11 pm

I actually encourage people to not only try to learn at least some of an Indigenous language, but to also speak out in favour of expanding Indigenous language programming. Part of the reason is is SO. HARD. for Indigenous people to access their own language, is the lack of classes available. So I’d ask, if you are interested in this, to not just take (learn the language) but also give (put pressure on politicians to support Indigenous language programming).

Anna · October 22, 2017 at 2:27 pm

Great article!

But it is untrue that Inuktitut has equal standing with English in Nunavut. English schooling is available up to Grade 12; whereas Inuktitut is generally only available up until Grade 3. When Inuit kids enter Grade 4, they start to lose their language.

For Inuktitut (and probably for many other indigenous languages), what needs to happen is clear from the evidence and from the Greenlandic example:

– Standardize the language and adopt roman orthography.

– Speak only Inuktitut to our children (don’t worry, evidence shows that they will pick up strong English because they will be constantly exposed anyway, through media etc.).

– Teach Inuktitut in 100% immersion schools (but to do this, we first need to standardize the language in order to develop an agreed-upon Inuktitut curriculum and to facilitate the training of enough Inuktitut-speaking teachers).

The #1 roadblock? Many Canadian Inuit Elders are against creating a standardized version of Inuktitut and adopting roman orthography, because they grew up with the “church orthography” (ie syllabics) associated still today with the Anglican Church.

To quote Inuit language advocate Jose Kusugak, “many Elders believe they will go to hell if they use Inuktitut roman orthography rather than syllabics”.

How to overcome this roadblock? All I can do is continually remind Inuktitut-speakers of the vision of Jose Kusugak, to create a standardized “Queen’s Inuktitut” so that Inuktitut can become the lingua franca of Nunavut and the Arctic.